The section on rowing is also in this column. Click on the link to go there

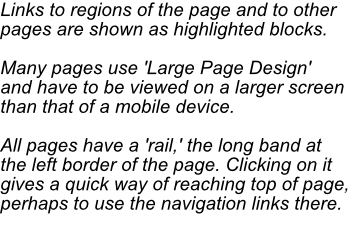

Above, Proms concerts: the Royal Albert

Hall.

My violin and viola. The violin

is a 'copie de' Stradivarius, according to a faded label you can just about

decipher if you look in one of the f-holes, so it's almost certainly a

French violin. It cost me something like £250, a very good instrument for

the money. The viola wasn't in the same price range. It cost me £40 -

another very good instrument for the money. This was a long time ago. They

must be worth much more now. But prices and commercial transactions are

sordid necessities as well as legitimate concerns for string players or

other instrumentalists.

Below, other views of the violin and viola:

Violas vary widely in size. My viola is average in length, 41cm (16") Below, a big viola, 43cm (17")

Prom 47 2018

The BBC Proms from the Royal Albert Hall

The BBC

Symphony Orchestra perform works by Elgar and Prokofiev, and are joined by

Pekka Kuusisto for the World Premiere of a new violin concerto by Philip

Venables.

- from the BBC announcement.

The composer Philip Venables contacted me to say that he was writing a violin concerto which included words as well as music. It would be a tribute to the Hungarian violinist Rudolph Botta. He'd seen a piece I'd written on an aspect of violin technique. He knew that I'd studied with Rudolf Botta. Could he include the writing in his violin concerto? I agreed, of course. My name, and the writing, are part of the work and were part of the performance, but only an incidental part, of course.

Rodney Lister wrote a good article on the concerto.

https://www.sequenza21.com/2018/08/the-proms-venables-venables-plays-bartok/

'Rudolph Botta, as Philip Venables wrote in his program note for his concerto Venables Plays Bartok, had a remarkable life ... He served in the Hungarian army during the Second World War, then was a member of the anti-Soviet resistance. He was sent by the Soviets to a labor camp in 1952, and during the time that he was there, was deliberately tortured and maimed so that he could no longer play the violin.'

I believe the fingers of his left hand were smashed with a hammer. When I went to his house, I saw a 'viola da gamba' there. This is an instrument with frets. It can be played without any of the precision which is essential when playing the violin. I didn't ask him about the instrument and he never mentioned it, but I think it's likely that his music making was confined to playing the viola da gamba. His career as a performing violinist had been ended, under horrific circumstances. His violin students could still benefit from his work.

Rodney Lister also writes:

After his release from the camp (as part of an amnesty following Stalin’s death), he started a music school in his hometown of Bonyhád. He was a leader of the 1956 Hungarian revolution before fleeing to the United Kingdom with his family. After a short stint as a window cleaner, Botta became a teacher at the Royal Manchester College of Music (now called the Royal Northern College of Music), where he was influential on the lives and training of countless violinists, including Marilyn Shearn, among whose students was Philip Venables.

'In November of 1993, when the young Venables was fourteen years old and preparing for his Grade 6 ABRSM violin exam, Shearn took him, along with three other pupils, to play for Botta. Twenty-five years later, when helping his parents move house, Venables discovered a copy of a long forgotten video tape of the masterclass with Botta which his teacher had made. That rediscovery caused Venables to begin a process of research involving Botta’s life and a consideration of the intertwining of lives, musical and otherwise, of teachers and students, and, eventually to the composition of Venables Plays Bartok, a work which could be considered a violin concerto, but which he also describes as a ‘radio music drama’. A BBC commission, it was given its first performance on the Proms concert presented on August 17th by BBC Symphony, conducted by Sakari Oramo.'

' ... The interaction of Bartok’s music with Venables’s, and of recorded spoken text, both the excerpts and bits of the actual coaching with Botta ... the clarity of the time shifts in the stories, and the control and balancing of density of textures, is always engaging and interesting, but the unfolding of aspects of one person’s life and how it and he then go on to impact other lives in various ways is completely compelling and very moving. It was impressive in its conception and its masterly realization, and completely satisfying as a total experience.'

Rudolph was kind and good natured and very generous in his judgments - generous to a fault, in my case. He said that I could become a violin teacher myself. This was mistaken, without a doubt. I practised hard - for hours every day, for most days of the week and I'd practised hard for my previous teachers - but I'd simply not been learning the violin for long enough and my aptitude wasn't good enough. No matter how many hours a day I practised, I could never have been good enough to teach the violin.

I didn't begin learning the violin when I was five years old or fifteen years old but in my thirties. I switched to the violin from the cello, but I only began learning the cello when I was 17. I didn't have very many lessons. When I did have lessons, I practised but in all the years I didn't have lessons, I did hardly any proper practice.

At the school, there was a dusty cupboard with a few musical instruments. Or was there only one? I wanted to learn the violin but there was only a cello there, so I started learning the cello. Our family wasn't rich or modestly endowed - there was absolutely no money available to buy a violin. The cello lessons were provided by the school. They were either free or cost hardly anything - I can't remember which. I did have enough money to go to string quartet lessons. They didn't cost very much - the benefits of sharing the cost between four people.

The teacher was abysmal, hopeless, but the

experience was wonderful. I treasure the memory of that time, but not of the

teaching. There wasn't any teaching

to speak of. The three works I played in the short time I had 'lessons'

included a Schubert quartet, his quartet No. 10 in E flat major, D87, a

lovely early work. The other two were Mozart's quartet K387, which was a

revelation, and remains a revelation, and Mozart's quartet K458, with a

profound Adagio.

I was lucky too in the works I played in the very small

cello section of the school orchestra, which gave me my first experience of

playing in public concerts. The concerts included

Mozart's Linz symphony and Beethoven's Symphony No. 1, each, in its way,

enthralling. The music teacher who

conducted the orchestra was someone with musical values. He didn't teach me

music. I'd given up music as soon as I could, at the age of 12. I didn't have much aptitude for the subject.

Later, but not that many years later, I joined an orchestra, a much better one, and played in public concerts. The works included Mozart's Prague Symphony and the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola, Beethoven's seventh symphony, Tchaikovsky's Variations on a Rococo Theme for cello and orchestra. The soloists in the works with solo violin, solo viola and solo cello were members of the Lindsay string quartet, which had a worldwide reputation. Rehearsals for the concerts and the concerts themselves - above all, the concert that included the Sinfonia Concertante - were amongst the best experiences of a time that was difficult for me.

The cello travelled down to London with me - I lived there for just over four years. The cello accompanied me when I was homeless. The landlord was breaking his mortgage agreement by letting his house out. The tenants didn't know that but one day, we did find out and soon after, I went to the county court with another tenant to see if we could influence the decision to evict us. Of course, we couldn't. The tenant who went with me said, 'So far as the court is concerned, we can sleep in the park, then?' I forget the exact words of the judge but he made it clear that that was fine by him.

We went back to the house and soon after the bailiffs arrived. Then, I was on the street with a suitcase in one hand and the cello in the other - everything I owned. The landlord was ready to allow us to sleep on his floor, as we'd paid the rent regularly, but I was the only one to take up his offer. I found another place to live quickly enough, so I never had to go looking for a derelict garden shed or a sheltered alleyway to sleep. I was none the worse for that particular experience.

I liked that cello but I was never fond of it, because I wasn't all that fond of cello playing, for daily practice - even though the experience of playing the cello in works of the repertoire had been a transcendent experience. I was able to play some works in isolation which were very satisfying to play - the Bach suites for solo cello, but not all the parts. There were sections which were too difficult for me.

The performance of an opera can never be definitive. Opera performances on the stage are composites, made up of music, the instrumental music of the orchestra, the singing of the soloists and the chorus, in many or most cases, sets and costumes. Strengths in any of these contributions can be accompanied by weaknesses.

But performance by a solo instrumentalist of a work written for solo

instrument is subject to different degrees of success in different parts of

the performance - and obviously subject to different opinions, with

disagreements about the success or failure or the admixture of success or

failure. The performances of the cellist Mischa Maisky of the Bach cello

suites arouse different points of view

but there seems to be agreement that his tone is superb and that these are

'romantic' performances, not in the least 'historically informed'

performances. I like his performances for some sections of some of the

suites but no performance of all the suites can be definitive.

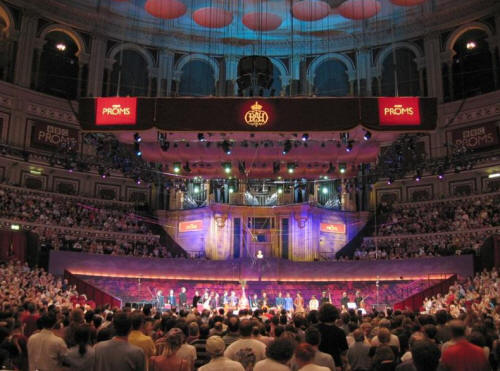

Below, Mischa Maisky

I never joined another orchestra as a cellist. Eventually, the cello was stolen from the house where I lived and where I still am. It was included in my insurance policy and I claimed what I had paid for it, many years before.

I played the violin in an orchestra for a short time and played in one or two public concerts but they weren't concerts where the pieces interested me particularly. I've felt no urge to join any other orchestra. If I had, I would have preferred to play the viola rather than the violin.

When I became a violinist, I played the Bach partitas and sonatas for solo violin. These are generally much more difficult than the cello suites. I had to leave out far more of the 'difficult parts' than in the case of the cello works. The Chaconne of the D minor partita is known for its fiendish difficulty. I've played some parts of the Chaconne, but not all that much, and none of it well.

'Violin and Viola' is one of the outstanding books in the series, 'Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides,' by Yehudi Menuhin, a violist as well as a violinist, and William Primrose, a violist who could also play the violin, even if he preferred to concentrate on the viola almost exclusively.

Chapter 7, 'Repertoire and Interpretation,' like other chapters, has so many insights, often very deep insights. The obvious point is made that 'Music began with improvisation. Then only gradually did notation become more precise ... ' but the ensuing discussion goes far beyond the starting point.

The section, 'The versatility of the violin' is wide-ranging. Some samples:

'The violin has been, and still is, the most universal of stringed instruments ... The violin is very suited to gypsies ... The violin is at home in the classical music of India ... The violin is at home on the moors of Scotland, on the plateaux of Norway, in the Blue Ridge mountains of America. The violin is at home in each Russian, Polish, and Rumanian village ... '

As in Klezmer music, which has its roots in Central and Eastern Europe, music which is mournful, evocative, energetic, virtuosic, joyous, wild, irrepressible, the linkage with improvisation always obvious.

Below, a Klezmer band with the common, if not characteristic, instrumentation - violin, clarinet, double bass and accordion. Also included, very often: percussion. Below, a Klezmer band from Lublin, Poland.

I've listened to many of the recordings of the Budapest Klezmer band - which includes a keyboard player and trombonist - such as this rousing, energetic piece,

'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kCLlOwlZ5zs

Daniel Hoffman is an outstanding Klezmer violinist. A sample:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVtIl3dqDbM

A Yiddish song with a violin included in the accompaniment:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HtrQFVw_8Ag

The Yiddish text is provided, with an English translation. This is the beginning of the piece:

Ich bin a Bucher jîng în frailech, ich fil sech gît,

es bengt sech mir nuch Libe,

es bengt sech mir nuch Glik.

Ich vill gain in alle Gassn în vill schrain: Gewalt!

A Maidale git mir bald!

But my interest in the baroque, classical and post-classical periods far exceeds my interest in any other genres.

For a long time, I've been a listener, not a listener as well as a player. No matter how good the player, if the player stops practising, the very good player becomes a very poor player. If the player is a poor player and stops practising, then the results are shocking. I've so many demands on my time, uses for my time and I couldn't possibly find the time and the energy to start practising again. If I did, I'd have to neglect other things which are very important to me. Spending hours every day or most days practising the violin would be absolutely out of the question for me.

Below, the birthplace of Mozart in Salzburg and a panorama of Vienna from the Donauturm, both of immense importance in the history of music and hideously compromised, as willing centres of Nazism. Mozart hated Salzburg, but Salzburg has profited from its association with Mozart, of course.

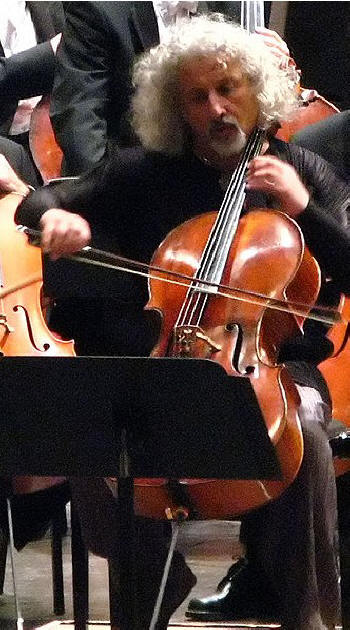

Below, a boat of the club I rowed for.

Below, the kind of setting I prefer for rowing. Rowing on the River

Wear.

Or this - a rowing eight training on the River Tyne

Rowing was a brief episode. Rowing was never very important to me, at the time I rowed and later. I've next to no interest in the kind of rowing I trained for, in a rowing eight, the kind of rowing practised in that well-known competition, the Oxford and Cambridge boat race.

If I lived near a lake and had a small rowing boat, it would be completely different. Rowing would be a passion and I'd want to take to the lake often. Rowing is a superb form of exercise, of course, exercising the arms as well as the legs. In this, it resembles cross-country skiing but rowing is harder, not technically but in its demands on the body, since masses of water have to be pushed and as long as the race lasts or the boat is moving fast through the water in training, the intensity of the work has to be experienced to be believed. In the case of cross country skiing, unless the skier is making a very long and difficult ascent, there are periods of rest or relative rest, if there are ascents there will be descents. If the skiing is being practised in atrocious weather conditions then obviously, the work can easily be much more demanding than in rowing.

I'll only give a little information here, without mention of place or time, except for what I've already mentioned, the fact that it was a brief episode, lasting just under two months. In that time, I did train hard - six days a week, for two hours a day or more. Towards the end of that time, the boat I trained in competed against something like twenty other rowing teams and our boat did win the competition.

Rowing has a technique but overall, a technique which is less involved, less interesting than the technique of so many other sports. It wouldn't be true to claim that rowing is infinitely less intricate and interesting than football, but that's only because that would be a misuse of 'infinitely.' Instead, I'd simply say that there's no comparison between rowing and football and that rowing is far less important as a sport.

On the other hand, rowing is practised in settings which have far more interest for me than the setting for football matches. I feel a strong affinity for water, for rivers, for lakes, for the sea. If I can't commune with any of these, a stream will have to do. The wonderful smoothness of competitive rowing can be soothing, to an extent, even when the boat is being driven hard, but the smoothness and gliding are intermittent, though regular. There's a rhythm of rowing, the alternation of propulsion and gliding.

Taken as a whole, the rhythm is much more harmonious than the rhythm of football, even though football matches have periods when the ball is propelled, driven forwards by the rhythmic action of the feet. Football matches will also have periods of stasis, when the ball is kicked out of play, when play stops for fouls and other reasons. The spectator's experience of a football match in most cases will include watching humdrum episodes, short or long or very long episodes, messy action, stopping and starting, the experience of intense and pleasurable tension, reversals of fortune, thrilling moments, sometimes thrills which seem to go on and on, cathartic experience, and more.

Football is far more varied than rowing. In rowing, there's teamwork without any possibility of independent action. In football, there's teamwork and independent action, both the teamwork and the independent action taking so many forms and variations.

The suspense of rowing is often short lived. One boat in a race gains on another. Will it maintain its lead? Will the crew tire, will the cox make a mistake in steering, getting too close to a bank, perhaps? There can be shifts in fortune for a time, sometimes for the duration of the race, almost, so that it's in doubt which crew will win. But often, one boat is so far behind the other that it's very, very unlikely that it will win.

Although football has comparable situations - a team which is losing by 4-0 at half-time is very likely to lose the match - there can be astounding come backs and the suspense offered by football matches, or so many of them, is of a different kind, a higher order.

I've only ever attended three football matches but I do follow Sheffield Wednesday football matches. . I'm disappointed when the team loses and happier when the team wins. I follow the team quite closely. The fortunes of the team interest me very much. This is a strong interest, but not one of my stronger interests.

As for the Oxford and Cambridge boat race, it's a competition where so many of the competitors have intellectual strengths, to a greater or lesser extent, but a competition which offers next to no scope for the exercise of the mind - for the rowers. Football offers far more possibilities for thinking, including inspired thinking. The analysis and commentary before and during football matches, but most of all after the matches, is very often of a high order, very impressive. The analysis and commentary which are associated with rowing competitions can never have anything like this quality.

I've never been a spectator at the Oxford and Cambridge boat race and never had any wish to be a spectator, but in my experience, my limited experience as a competitor and my limited experience of watching amateur rowing teams, the spectators give a very favourable impression, very enthusiastic, delightful, even.

Soon after I started rowing, in a boat with an inexperienced cox - he'd started coxing at the same time that I and the others started rowing, our boat collided with the University boat training on the river. I've a vivid memory of the coach / trainer pedalling fast and furiously on his bike towards our cox and saying sternly, 'In accordance with the statutes of the University of Cambridge I hereby fine you five pounds.' This was a long time ago. Five pounds was a lot of money in those days.

Rowing necessarily allows next to no freedom of action to everyone in the boat except the cox. I exclude, of course, the theoretical freedom which every rower has to suddenly stop rowing and to shout out 'Stuff this. I've had enough' or something similar or something very different, the theoretical freedom to get up from the sliding seat and jump into the river.

The rower isn't a galley slave but despite the vast differences, the rower in a rowing eight is constrained, necessarily constrained. The rower has to keep rowing until the instruction comes to stop rowing, or the race is over.

One reason for including rowing on this page is to be able to compare rowing with orchestral playing, or playing an instrument in a quartet, or with a pianist, or performing a piece for solo instrument but with an audience.

When I was playing the cello in an orchestra, I and the other players had to keep playing until the conductor instructed us to stop - this would only happen in a rehearsal. Obviously, orchestras are stopped very often in rehearsal so that the conductor can make a point. In a public concert, we had to keep playing until we got to the end of the work.

All this was no hardship, caused no difficulties. Playing in an orchestra was an immense privilege, immensely important to me - not only whilst it lasted, which wasn't nearly long enough, for a variety of reason but in memory. As for rowing, rowing for a couple of months or a little less was all I needed, just enough time to sample the activity, no more.

Above, cross-country skiing, Telemark turn

Attribution: Kjetilbmoe, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>,

via Wikimedia Commons

Above, cross-country skiing, Telemark turn

Above, cross-country skiing, the diagonal stride

Some of the images above show skiers using the 'diagonal stride' or the 'telemark turn.' The diagonal stride is a basic technique of Nordic skiing for skiing on the level as well as uphill. The telemark turn is an important turn used in Nordic domnhill skiing. I've used these techniques as well as many other techniques, obviously, but none of the images above show me. The telemarkers above are using equipment I never used. I've a strong preference for much simpler equipment than these telemarkers are using. I had no interest in photography at the time I was an active skier and took no photographs at all of my skiing activity.

None of the scenes above show places where I've skied. The third image above shows tracks made by machine to make cross-country skiing easier. I've never used tracks like those. The frozen pond shown above is similar to the frozen pond I've used for skiing in my neighbourhood. I only skied there in a period of intense cold, when the ice was thick and completely safe. The last picture above shows Edale in Derbyshire. I've not skied in that particular place but I've skied very near to it. I skied in open, undulating or hilly terrain but I've also used the same simple equipment on the piste, on the slopes used by Alpine skiers, with mechanical lifts.

Some information for people not familiar with the difference between Alpine and Nordic skiing. Alpine skiing is skiing where the heel as well as the toe of the boot is clamped to the ski by means of a binding with a release mechanism, breaking the connection between boot and ski in case of a fall, to prevent injury. The equipment is heavier than the equipment generally used for Nordic skiing and it can only be used for skiing downhill.

Nordic skiing is skiing where only the toe of the boot is clamped to the ski. The heel is free to lift. This allows the skier to ski uphill as well as on more or less level ground and on undulating terrain. The skier has no need of mechanical help but sometimes makes use of it. In some places, helicopters are used.

There are various forms of Nordic skiing, with widely varying equipment. Racers use thin skies for speed on level or undulating ground and often ski in the machine-made tracks. This form of skiing has never interested me. Telemark skiing is a form of Nordic skiing using 'telemark turns' and usually other kinds of turn. The name comes from the Telemark region of Norway. Often, telemark skiers use equipment quite similar to Alpine skiers, wide skies and heavier, elaborate boots and bindings, although telemark turns are perfectly possible with much narrower skies and less elaborate boots and bindings, the equipment I always used. Telemarking is only possible with Nordic equipment, with the heel free to move.

Ski jumping is another form of Nordic skiing. After the take off and flight, the telemark landing (one foot in front of the other) is a graceful way to finish the jump. Only a minority of Nordic skiers ever ski jump and I'm certainly not one of the minority.

Above, my cross-country skis and ski poles. The skis are much narrower

than the Alpine skis used, most often, for skiing on the piste at ski

resorts. The poles are longer than the poles used in those forms of

skiing. The skis aren't as narrow as the cross-country skis used for racing

and for use on prepared tracks. I've found the skis very versatile, usable

in soft deep snow and hard-packed snow - not nearly so good on ice,

generally, but they were superb for working up speed on the frozen pond. They have a base which prevents or reduces

slipping when going uphill but also a good ski for downhill skiing,

including the Telemark turn.

I haven't done any skiing for a long time - the winters have been

generally mild for so many years. When I started to ski, there were quite

often extended periods in the winters when a great deal of skiing was

possible. I prefer skiing in this country to skiing abroad and my

finances wouldn't have allowed me to travel to the Alps or other ski areas

that often. A short visit to Poland one winter included a visit to Zakopane

in the Carpathian mountains and there was plenty of snow there, but my main reason

for visiting Poland was to visit other places, for specific reasons that had

nothing to do with skiing or the snow conditions.

I've never

pre-booked an hotel or a campsite and I've never been on a package holiday.

I haven't been away on a holiday of any kind for about twelve years. When I visited Poland, it was

winter. I arrived in Krakow after the coach journey from London and found a

cheap hotel quickly. When I went to Zakopane I found a room to stay almost

immediately.

Years before that, when I visited Oslo in winter, after

a direct train journey from London, I wasn't so lucky. It was snowing and it

was cold - just what I like in winter. It was hours before I found an hotel

that was open. In the Norwegian capital, as in so many much smaller places,

I found, hotels shut down for the Christmas and New Year Period. I soon

found that the Norwegian for 'closed' is 'lykket.' I could probably have

found a place more quickly - perhaps there was a place open in the

train station that could locate a room for me, unless that was 'lykket'

too. After nearly two days of train travel and four

hours of walking in the snow, I found a place to stay. After that, I went back the

way I came and stayed in Copenhagen and then to Bruges. I think this visit

to Oslo was perhaps the least successful journey I've ever made, or perhaps

not. I didn't go to any Norwegian ski area. It wasn't so much that I had no

interest in skiing, skiing was something I'd never thought about. I saw so

many people carrying cross-country skis on the visit. It may well have given

me the idea to start cross country skiing not so many years later. If it did

give the idea, then it was far from being a wasted journey.

I haven't

kept up to date with developments in skiing.. The binding on this ski won't

be one of the bindings used now.

Learning the technique and practising the technique of the diagonal

stride, and some other cross-country techniques, is possible using short

roller skis, a form of skiing on hard surfaces. I used to own roller skis

but didn't make very much use of them. I preferred to wait until winter and

ski on snow, not on roads.

I started learning the cello, and then the violin and viola, far too late to have any hope of becoming a very good player. The same with cross-country skiing. I had cello, violin and viola lessons. I've never had skiing lessons, apart from a lesson or two on roller skis. Apart from that, I'm completely self-taught. I've been very diligent in studying technique, including the technique of downhill cross-country skiing, in particular, what's known as the 'Telemark turn.' I've skied in the Alps as well as this country, but the opportunities haven't been plentiful.

When I started skiing, there were winters in this country which were much colder and snowier than they have been for a long time. Those winters are a distant memory. Even Scottish cross-country skiers, even the ones based in the Highlands, will have had skiing seasons much shorter than they would have liked.

All the greatest joys I've experienced as a cross-country skier have come from skiing in the hills near here, foothills of the Pennines, and the hills over the county border in Derbyshire, in particular at Edale, the start of the Pennine Way. These experiences of deep joy aren't in the least peripheral for me, any more than the experiences of deep joy which have come from string playing - even though in both cases, the activities have occupied only a very small percentage of my time.

The experience of skiing over a frozen pond, again and again - the pond is ten minutes walk from here - during a very cold winter when the ice was thick and completely safe could never have become a frequent experience. So too the experience of seeing a white-furred hare walking delicately on the smooth snow on the hills further away, the expanse of smooth, untouched snow stretching in all directions until stopped by the dry stone walls enclosing the fields, the experience of moving to fresh fields, leaving behind the snow meadows I'd marked with the trails of my skies, the swish of the skies through powder snow - a rare form of snow here.

The dusk falling on the snow, fresh snow falling on the fallen snow, the weather becoming bleaker but the elation of skiing untouched, the experience of skiing down a steep slope and skiing to the top of the slope again and again. The emptiness of the Yorkshire and the Derbyshire hills and the fullness of experience that comes from being in those hills.

I've skied in the Alps, but only on two visits. I can't even remember the name of one of the two ski resorts I stayed in. This was in Spring, the snow was retreating and the resort itself was largely without snow. The other resort was Chamonix, below Mont Blanc. This was much better. I arrived at Chamonix when it was dark. As with the other resort, I hadn't arranged an hotel. I had no intention of staying in an hotel. I've not stayed many nights in an hotel in total, anywhere. I did sometimes when I've travelled in the United States, but often I slept on the train. When I travelled in Canada, I camped. This was in 'bear country.' The campsite gave an informative leaflet with some hints on what to do if attacked by a bear. By following the advice, the leaflet assured the reader, a bear attack could result in only 'minor injuries.' There were wooden structures dotted about the place, with a rope hanging down. You attached a bag with your food inside and hauled the bag up so that it was beyond the reach of a bear. If you left food in the tent, then a bear could shred the tent to get at the food, and perhaps shred the camper as well.

I did see a bear there, and it was nearby, but it was only a young one and no threat at all. A fully grown bear would have been a different matter.

I've done a lot of camping. Before I learned to drive (at the age of 40), my procedure was to get the rail ticket or the coach ticket and find a campsite on arrival. If I've not been able to find a campsite, as happened when I arrived at the Isle of Skye, I went out to the moors - they may have a different word in those parts - and used a simple bivouac bag to sleep under the stars - or the clouded sky, rather.

Back to Chamonix. All went well. I found a campsite without any difficulty. There was only one other tent there. The campers were British. After the first day or two, there was the problem of wet socks, although it was only a minor problem. Snow getting into my boots melted, of course, and socks became sodden quickly. It didn't interfere with the satisfactions of the stay. In actual fact, they were far more than satisfactions but they never equalled the rapture of skiing in South Yorkshire and Derbyshire.

The experience of speed over much longer distances than my local area could offer was thrilling, though. I wasn't interested in the cross-country trails which seemed to be available, on level terrain and not very steep terrain. The chance to ski Alpine downhills was all I could think about.

One of my books recommended use of ski resorts, or ski areas, with mechanized uphill transport as an efficient way of gaining dowhhill experience without the time-consuming need to get back to the top of the slope by muscle power. I didn't learn very much from my visit that made me a better skier. I launched myself again and again from the top and picked up so much speed that trying Telemark turns was out of the question - for me as a skier without vast experience of these conditions, with no experience of these conditions. I stopped by falling on my back. Cross-country skis with their simple bindings holding the simple lightweight boots of the skier, are much more difficult to control.

All of this, the camping, the skiing, the terrain, are far distant from the world portrayed, unforgettably, in my book on cross-country downhill, set in the massive mountains of the American and Canadian Rockies. The mountains towering above Chamonix are every bit their equal, but I wasn't equipped for a solo adventure in those peaks. I did well, I think, to leave Chamonix in one piece, without breaking my neck, my back or a limb. I was the only cross-country skier venturing on to the piste, I think.

Alpine ski equipment has never interested me at all. I would rather not have skied at all rather than have to rely upon those aids. And my opinion of mechanical transportation for Alpine skiers is that they're miracles of modern ingenuity, needing tremendous efforts to install, but they really do disfigure a mountain. Cross country ski equipment too could be called a miracle of ingenuity but I far prefer its relative simplicity.

The tracks in the third photograph above are made by machine. They guide the skis of people who have narrower skis than the skis I've used. Racers use narrow skis. I've no interest in racing or in slower travel using those tracks. I've never used the narrow skis or the tracks. I've always skied using Telemark skis, for going uphill and downhill and on level ground. I've wanted to ski in places where the machines don't go. I use the past tense because my skiing activity has had to end.

The tracks shown in the photograph have an attractive form but this seems like the cross-country equivalent of a motorway. I realize that there are different tracks for different kinds of skiers. If it attracts hordes of skiers, that isn't a place that would attract me, even if the landscape itself is attractive. I've no interest in what's called 'citizen racing,' those events that attract thousands of entrants, or ski marathons.

All the videos except for one, the last one in the list here, are short - very short.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CUxS9B0IjUQ

Below, view as night falls

Below, cross country skiing in the Zakopane area

I stayed in Zakopane for a time during my visit to Poland, but I didn't take my skis. My visit to Poland lasted only a week and before I went to Zakopane I stayed in Kraków. My main reason for visiting Poland was to visit Auschwitz, which I did, and the visit has left a lasting impression, as it should for every visitor. My visit to Poland left a lasting impression. This is a country I like very much, a country I respect and admire very much.

Kraków, unlike Warsaw, suffered hardly any damage during the Second World War. The devastation in Warsaw was on a horrific scale. Krakow is a very attractive, unspoilt city. I haven't visited Warsaw. An extract from the section on Warsaw in 'The Rough Guide to Poland,' by Mark Salter and Jonathan Bousfield which shows wonderful understanding:

'Travelling through the grey, faceless housing estates surrounding Warsaw (Warszawa) or walking through the grimy Stalinist tracts that punctuate the centre, you could be forgiven for wishing yourself elsewhere. But a knowledge of Warsaw's rich and often tragic history can transform the city, revealing voices from the past in even the ugliest quarters: a housing estate, the one-time centre of Europe's largest ghetto, the whole city a living book of modern history.'

Below, buildings in Warsaw constructed after the devastation of the war, such attractive buildings, such attractive places.

My view of Zakopane is very favourable. This is not a particularly attractive town, but it's a good ski resort and a very popular ski resort. Whatever attractiveness they have, very popular ski resorts tend to have some of their attractiveness diminished by the overcrowding. Poland has only one ski resort of any size, and this is it. It's too popular for its own good. In spite of that, I like the place a lot. What I saw of the Carpathian mountains, and I would like to have seen much more, interested me and impressed me. I went up the Gubałówka hill. The viewing conditions were far from ideal but the snow conditions were superb.