introduction

Courageous men, courageous women, and animals

The horses: terror and trauma

Horse disembowelling

and the 'Golden Age'

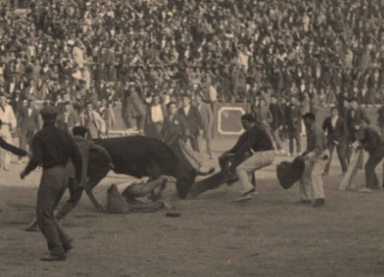

The bull

Courage of the bullfighters - illusions and distortions

Bullfighting: the last serious thing in the modern world?

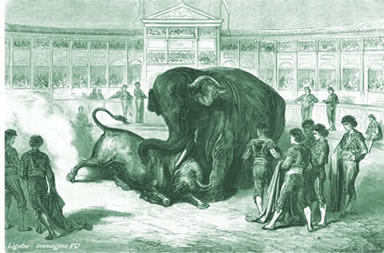

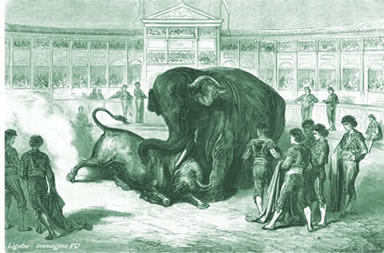

Bulls, elephants and tigers

Bullfighting and comedy

Fadjen, a

fighting bull

paigning techniques

Three Spanish restaurants

Human welfare and animal welfare

Other forms of bullfighting

Pamplona: a proposal

Bullfighting and tourists

Andy

Goldring, 'Permaculture Educator,' attends a

conference

in

San Sebastián, Spain

The Duncan Wheeler Case

La

Route de Sang: contre la corrida en la France,

en

français

A L Kennedy on bullfighting

Fiske-Harrison: The Baboon and Bull Killing Club

Alexander Fiske-Harrison's blog: The Anti-blog

Alexander Fiske-Harrison: the bullfighter-comic

Antalya Nall-Cain: commentary on the writing of

Sarah Pozner, five star fiancée

Stanley Conrad and the infant Jesus

Giles Coren: Pensées et Réflexions d'un

Gourmet

Daniel Hannan (who also calls himself 'Christopher North'): the 'tender relationship' of matador-bull'

The Club Taurino of London: fighting talk

Orson Welles: who changed his mind

Michael Portillo, speaker

See also

Carmen and bullfighting

Seamus Heaney: ethical depth?

Women and bullfighting

Animal welfare and activism

Ethics: theory and practice

Introduction

The

bullfight I discuss on this page is the 'corrida,' the bullfight of Spain and some other countries,

but I discuss very briefly other forms of bullfighting.

I explore

the mind of the bullfighter and the bullfight supporter, discussing in detail

their conviction that bullfighting is a developed art, that it requires special

courage and other deeply misguided views. This discussion of bullfighting

gives new information and puts its cruelties in a wide context.

For example, I acknowledge the courage of bullfighters

but make clear that this courage is limited, far surpassed by the courage

shown, for example, by high-altitude mountaineers and in the war experiences

of countless people. I provide some instructive statistics, which show that

the risk of being killed in the bullring is negligible.

The sufferings of the

horses in the bull-ring have a context: the enormous, never-to-be forgotten

indebtedness of humanity to horses in times of war and peace. Instead of

this suffering being secondary or of no account at all (the usual attitude

of apologists for the bullfight such as Hemingway), it becomes a central

objection to bullfighting. The suffering of the horses is often a prominent

part of the anti-bullfighting case but I give an extended argument. The

section after this, The Golden Age of Bullfighting,

is about horses in the bullring too. It gives information about the

astonishing number of horses killed during bullfights before 1929 but I try

to show that this is of far more than historical importance.

The multiple stabbings inflicted on the bull are a matter of common

knowledge to opponents of bullfighting. I document and

discuss these, of course. An extract from my discussion: 'Alexander Fiske-Harrison saw a bull stabbed

three times with the 'killing sword' but still alive, and then stabbed

repeatedly with the descabello. According to the 'bullfighting critic'

of the newspaper 'El Mundo' who counted the stabbings, the bull was

stabbed in the spine seventeen times before it died.' Alexander

Fiske-Harrison went on to kill a young bull himself, with hideous cruelty. Like this matador,

he stabbed it three times with the 'killing sword.' The bull was still

alive, with the sword embedded in its back. It too was stabbed in the spine

to kill it. The number of blows isn't recorded. I include an extended

review of his book Into the Arena.

Bullfighting apologists

claim that bullfighting is an art rather than a sport, pointing out that it's

reviewed in the arts sections rather than the sports sections of newspapers.

I expose the artistic pretensions of bullfighting. I quote defenders of bullfighting who have made revealing

admissions about the artistic limitations of bullfighting.

In fact, every aspect

of bullfighting is shown as limited. Ignore the sick and decadent claims to

importance, the romanticized exaggeration, the flagrant myth-making.

I don't confine my attention to animal suffering. I argue

that the adulation given to bullfighters by bullfighting supporters

distorts. The

matador Padilla, for example, has been portrayed as a heroic figure.

He was injured in the

bullring and lost an eye. This is a bullfighter whose recklessness has been extreme. Padilla is still alive - not so Marie Colvin, the

journalist who was hit by shrapnel during the conflict in Sri Lanka

and lost an eye and who has now been killed by shellfire from Syrian forces.

Abolition of bullfighting is long overdue. Bull-baiting

and bear-baiting were abolished in this country in 1835. On other pages of

this site, I write about some of the cruelties, abuses and injustices to

people which were prevalent before and in some cases after this time, such as the 'bloody code,' which punished

a large number of offences in this country with public hanging (two thirds of the hangings

were for property crimes) and the sufferings of adults and children during

the industrial revolution, in particular the dangerous and back-breaking work

of men, women and children in the mines. But the tearing of a bull's or bear's

flesh by powerful dogs for public entertainment - the teeth and claws of the

bear pulled out beforehand to make it more helpless - was no minor matter.

Bull baiting and bear baiting were indefensible and their abolition was necessary.

In countries of modern Europe and the bullfighting

countries of Latin America, animals with swords embedded in their backs are

made to twist and turn by flapping capes, in the hope that the sword will

sever a vital organ and bring about the death of the bull - a procedure

which so often fails. Even when the animal is killed by the sword at once, it will

previously have been stabbed a minimum of seven times. I believe that bullfighting, which,

unlike bull-baiting and bear-baiting, has artistic pretensions, is indefensible in both its Portuguese and Spanish forms

and ought to be abolished. But action against bullfighting should be with

full

awareness of context, the context of preventable suffering, animal suffering,

such as the suffering of factory-farmed animals, and human suffering.

I've made every effort to ensure that the information I

give concerning bullfighting and the other spheres I discuss is accurate.

I'd be grateful if any errors are brought to my attention - and, of course,

relevant information not included here, different interpretations of

evidence, objections and counter-arguments.

This page gives an introduction to the subject. I give

much more space to the arguments against bullfighting, the reasons why there

should be action to end bullfighting, than to the forms that action takes

and, I argue, should take, although I do comment on some campaigning

techniques.

So much writing in support of bullfighting is suffocating

in its exclusion of the world beyond bullfighting. I see no reason why my

anti-bullfighting page should follow this example. The supplementary

material I include goes far beyond the limited world of bullfighting.

For example, I give reminders of human courage and artistic achievement which owe nothing

to bullfighting and discuss or mention natural beauty, wildlife, wildlife conservation and other

topics. The starting point in every case is a bullfighting topic.

Professor Duncan Wheeler, whose multiple, and deeply

disturbing failings (as I see it) are discussed at length in the first

section of this column, studied Philosophy as well as Spanish for his

undergraduate degree at Oxford. He may well know of this, section 593 of

Ludwig Wittgenstein's 'Philosophische Untersuchungen' ('Philosophical

Investigations'):

'Eine Hauptursache philosophischer Krankheiten - einsitige

Diät: man nährt sein Denken mit nur

einer Art von Beispielen.'

'A main cause of philosophical diseases - a one-sided

diet: one nourishes one's thinking with only one kind of example.'

I quote this in various places on the site and give it

much wider applicability (in terms of my theme-theory, the

application-sphere is much less subject to {restriction}.

It can be applied to (it's application-sphere includes)

bullfighting as a discussion-sphere and the range of arguments and evidence

employed in discussion of bullfighting.

Bullfighting isn't self-evidently one of the most

important of all ethical/aesthetic issues but to focus entirely on 'Big

Issues' or the Biggest Issues would be a mistake, except for people who have

very good reason to focus on them, perhaps to solve Big or Very Big

problems. Ecological investigation which focused only on the most widespread

species in a habitat would be a Bad or Very Bad mistake.

I see the need for a wide range of evidence and a wide

range of arguments to address the issue of bullfighting, and I find every

reason to believe that the evidence against bullfighting is overwhelming.

As for Wittgenstein's 'Philosophische Untersuchungen,' I

vastly prefer the 'Tractatus Logico-philosophicus,' a work I've given my

close attention over a very long period of time.

The

horses: terror and trauma

Petos ('protective mattresses') of picadors' horses.

Ernest Hemingway, 'Death

in the Afternoon:'

'...the death of the horse

tends to be comic while that of the bull is tragic.' He relates the time when

he saw a horse running in the bull-ring and dragging its entrails behind it,

and makes the further remark 'I have seen these, call them disembowellings,

that is the worst word, when, due to their timing, they were very funny.'

He

was writing of the time when the horses of the picadors were completely unprotected.

A decree of the government of Primo de Rivera in Spain ordered that picadors'

horses should be given a quilted covering 'to avoid those horrible sights

which so disgust foreigners and tourists.' This took place in 1929. Note that it wasn't bullfighters

or bullfight enthusiasts who called for this protection. If they had, it would

have been something in the balance to set against their depravity, but no.

Before that time, it was common - in fact, usual - for far

more horses than bulls to be killed in a bullfight - as I explain in

The Golden Age of Bullfighting, as many as 40.

Disembowelling

is uncommon now, for the horses of the picador and the

rejoneador or mounted bullfighter.

However, Hemingway was

clear about one thing. 'These protectors avoid these sights and greatly decrease

the number of horses killed in the bull ring, but they in no way decrease

the pain suffered by the horses.' And, in the entry in the Glossary for the

pica, the spear with which the bull is stabbed by the picador, 'The frank

admission of the necessity for killing horses to have a bullfight has been

replaced by the hypocritical semblance of protection which causes the horses

much more suffering.' One of the reasons is that 'picadors, when a bull, disillusioned

by the mattress, has refused to charge it heavily more than once, have made

a custom of turning the horse as they push the bull away so that the bull

may gore the horse in his unprotected hindquarters and tire his neck with

that lifting...you will see the same horse brought back again and again, the

wound being sewn up and washed off between bulls...'

Whether the picadors take

this action or not, the objective in the bullfight is to tire the bull not

just by spearing it with the picador's lance (although this is far more than

'tiring.' It's a vicious injury.) The objective is to tire the bull also by

exposing the horse to the force of the bull. So, horses in the bullfight are

crushed against the wooden barrier of the bullring, lifted, toppled, trampled

and terrorized, suffering broken ribs, damage to internal organs - treated

worse than vermin. The mattress may offer some protection against puncture

wounds but not against other injuries and it hides the

injuries which are caused.

Larry Collins and Dominique

Lapierre in their biography of the bullfighter 'El Cordobes' describe injuries

to horses during his 'career' - this was long after the adoption of the

'protective' mattress. Internal organs protruded from the bodies of the

horses. How were the injuries treated? The horse contractors shoved the organs

back and crudely sewed up the wounds. The organs still protruded, though,

to an extent. The protruding parts were simply cut off. The horses might well

last another bullfight or two. The authors - 'aficionados' - relate all this

in a matter of fact tone, without the least trace of criticism or condemnation.

From my review of A L

Kennedy's book, On Bullfighting,

quoting first from the book. She received the help of an aficionado

in writing the book, Don Hurley of the 'Club Taurino.' ('This book could not

have been written without ... the expertise and advice of Don Hurley.')

A L Kennedy 'Arguments are cited which state, reasonably enough, that the

blindfolded and terrified horse is currently buffeted by massive impacts,

suffering great stress and possibly broken bones.' She might have mentioned

the internal injuries which horses also suffer.

Even if a horse is lucky and suffers no broken bones or internal injuries, it can

be imagined what terror it will feel when blindfolded and led out to take

part in the parade before the bullfight,what terror it will feel when forced

to enter the arena to face the bull, what terror it will feel when it hears

and smells the bull, and the terror it feels when the bull, in its frantic

effort to escape, hits it very hard.

The first film I saw which

showed a bullfight included a 'rejoneador,' a mounted bullfighter. (The same

film also included horrendous footage of a bull which had obviously hit the

wood of the bullring very hard, with a horn hanging off, almost detached,

and almost certainly feeling severe pain - even before it faced the lance,

the banderillas and the sword.) The horse of the rejoneador isn't protected

in any way. The intention is that the horse's speed and agility and the skill

of the rider enables it to avoid the horns of the bull. Sometimes, the reality

is otherwise.

Jeff Pledge, on the methods used by Alain Bonijol, the French

supplier of picadors' horses: 'He has built, on a pair of wheels from some

piece of farm machinery, a kind of heavy-duty carretón, which has a pole

with a flat plate on the end sticking out the front. Several hefty blokes

shove it into the horse, who is wearing his peto, and try to push him over

or back ...' ('La Divisa,' the journal of the Club Taurino of London.) This

gives information not just about training methods but about the hideous

mentality of these people.

Since it's necessary, as

bullfight apologists admit, to injure horses in order to have a bullfight,

why, then - abolish the bullfight, and as soon as possible too, and not only

for the sake of the horses. Catalonia has shown the way.

Horses in human service have suffered horrifically, and continue to do so.

This is some necessary context for the horrific suffering of horses in the

bullring:

Hugh Boustead, a South

African officer, of an experience during the Battle of the Somme in the First

World War. (Quoted in 'Somme,' by Martin Gilbert):

'Dead and dying horses,

split by shellfire with bursting entrails and torn limbs, lay astride the

road that led to battle. Their fallen riders stared into the weeping skies.'

Dennis Wheatley, describing

an aerial bombing attack on the Western Front in December 1915 in his book

'Officer and Temporary Gentleman.'

'When the bombs had ceased

falling we went over to see what damage had been done. I saw my first dead

man twisted up beneath a wagon where he had evidently tried to take shelter;

but we had not sustained many human casualties. The horses were another matter.

There were dead ones lying all over the place and scores of others were floundering

and screaming with broken legs, terrible neck wounds or their entrails hanging

out. We went back for our pistols and spent the next hour putting the poor,

seriously injured brutes out of their misery by shooting them through the

head. To do this we had to wade ankle deep through blood and guts. That night

we lost over 100 horses.'

Without horses, or similar

animals, no developed human civilization was possible. Before the modern era,

their role in carrying loads (as pack-horses), pulling heavy loads and carrying

riders was crucial, all-important.

Horses of substantial

size as well as ponies went down the mines and were used well into the twentieth

century. They were stabled underground and lived the rest of their lives underground,

in complete darkness or almost complete darkness. From a display at the National

Coal Mining Museum: 'To the miners, the pony was a workmate. Together they

experienced the same conditions [back-breaking work, breathing in coal-dust]

and faced the same dangers [of explosions that mutilated or killed, of drowning

when the workings were flooded, and the rest]' After nationalization of the

mines, they spent 50 weeks of the year below ground but were given two weeks

holiday. A photograph of conditions in an American mine in the early 20th

century:

Gratitude, overwhelming

gratitude, is the only proper response. The horse: this is a species which

has benefitted mankind more than any other, which has earned, many, many times

over, the right not to be subjected to disgusting cruelty. These facts alone

should have made it unthinkable to subject horses to the cruelty of the bullfight.

The link between horses and humanity is ancient and central. The tradition

of bullfighting is not at all ancient. Bullfighting in anything like its modern

form is only centuries old. In France, the tradition is more recent still.

A fact often overlooked

is that, even after the development of mechanical means of carrying loads

and transporting people, horses continue to play their ancient role today,

as uncomplaining, useful - indispensable - beings. In many parts of the developing

world, they continue to be as indispensable as they ever were in Europe. Their

treatment is very varied. It may be as good as could possibly be expected

in desperately poor societies. It may, on the other hand, be vile, with avoidable

sufferings - and not only the vicious use of the whip, which leaves so many

horses with open wounds and scars. Often, there is the absence of basic care.

From the newsletter of a charity I support:

'Across the developing

world, thousands of brick kilns in poor villages and towns are churning out

millions of bricks to feed a growing demand for houses, hospitals and schools.

These blisteringly hot open-air factories are relentless brick-making machines.

Desperately poor workers and their horses, mules and donkeys are merely part

of that machine. For the workers, kiln life is tough enough, but for their

animals, these can be the worst workplaces on earth.

'Temperatures can hit

50 C, yet often there is little water or shade. Uneducated owners don't understand

their animals' needs and work them hard as they can under tremendous pressure

to meet production targets. Many animals are denied rest on 12-hour shifts

that see weary donkeys and horses hauling bricks by the ton across hilly,

pot-holed terrain.

'Donkeys, horses and mules

working in brick kilns suffer dehydration, exhaustion, hoof, skin and eye

problems, and a catalogue of other illnesses. They bear horrific wounds from

beatings and from falling down, and struggle with filthy, ill-fitting harnesses

and saddlepacks. Sadly, many who fall never get up again. Life expectancy

for kiln animals can be dreadfully short.'

George Orwell, in the

twentieth century, wrote of the ponies in parts of the Far East: 'Sometimes,

their necks are encircled by one vast sore, so that they drag all day on raw

flesh. It is still possible to make them work, however; it is just a question

of thrashing them so hard that the pain behind outweighs the pain in front.'

(From 'Down and out in Paris and London.')

Another dimension - and

another, even worse, dimension of horror - comes from the role of animals

in war. When cavalry was an active instrument of war, a period lasting millennia

rather than centuries - even as late as the First World War, cavalry had a

real if restricted role - then horses, like men, were injured and killed by

arrows, javelins, spears, axes, musket shot, rifle bullets, were blasted by

cannon and artillery, the link between horses and humanity again strengthened

by common suffering.

From the enormous documentation

available, here is one source.

From Franz Kafka, The

Diaries 1910-23:

'Paul Holzhausen, die

Deutschen in Russland 1812. Wretched condition of the horses, their great

exertions: their fodder was wet green straw, unripe grain, rotten roof thatchings...their

bodies were bloated from the green fodder.

'They lay in ditches and

holes with dim, glassy eyes and weakly struggled to climb out. But all their

efforts were in vain; seldom did one of them get a foot up on the road, and

when it did, its condition was only rendered worse. Unfeelingly, service troops

and artillery men with their guns drove over it; you heard the leg being crushed,

the hollow sound of the animal's scream of pain, and saw it convulsively lift

up its head and neck in terror, fall back again with all its weight and immediately

bury itself in the thick ooze.'

Although I concentrate

here for very good reason on the sufferings of horses, I never at any time

forget the human suffering. During the French retreat from Moscow, this was

extreme - but an extreme often approached or equalled before and after this

time. From David A. Bell's very searching book, 'The First Total War: Napoleon's

Europe and the Birth of Modern Warfare:' 'The men slept in the open, and in

the morning, the living would wake amid a field of snow-covered corpses. Lice

and vermin gnawed at them. Toes, fingers, noses and penises fell victim to

frostbite; eyes, to snow blindness.' The horses' suffering was extreme - but

again, an extreme often approached or equalled before and after this time.

'The starving soldiers' were desperate for 'the smallest scraps of food. Some

ate raw flesh carved out of the sides of live horses...'

According to the

historian David Chandler he lost a total of 370 000 men and 200 000 horses.

During the First World

War, there was approximately one horse for every two combatants and although

horses were not directly targeted, cavalry by now becoming less important,

they were still used on a massive scale to haul guns and waggons. About 400

000 horses were killed in the conflict. Many of them died, like the soldiers,

by distinctively new methods, by phosgene, mustard gas, chlorine gas. At Passchendaele

horses, like many of the soldiers, suffocated in the mud.

There are accounts by

soldiers who regretted that horses had been caught up in the conflict. The

account of Jim Crow, quoted in 'Passchendaele,' by Nigel Steel and Peter Hart:

'You hear very little

about the horses but my God, that used to trouble me more than the men in

some respects. We knew what we were there for, them poor devils didn't, did

they?'

In one of his last letters

before he was killed at Verdun, the German expressionist painter Franz Marc

wrote, "The poor horses!" On a single day at Verdun, 7 000 horses

were killed.

At the end of the conflict,

the martyrdom of horses was far from ending. Large numbers of them were sold

to work in the Middle East and were worked to death.

Even after the development

of mechanized warfare and mechanized transportation, horses were used often

- in enormous numbers as late as The Second World War. I think of a photo I have of 'The Road of Life.' For 900 days, during the

Second World War, Leningrad was besieged by the Germans: an epic story of

heroism, and starvation, which accounted for most of the deaths during the

siege, at least 632 000 and perhaps as many as a million people dying. With

the capture of Tikhvin, it became possible to develop an ice road, 'The Road

of Life,' across frozen Lake Lagoda to supply the city. The photo shows gaunt

horses dragging sledges across this ice road.

Horse disembowelling and bullfighting's 'Golden Age'

In each twentieth

century Spanish corrida (bullfight) before 1929, six bulls were killed, as

is the case now. In each of these bullfights, how many picadors' horses do

you think were killed? One horse per bullfight on average, not as many as

one, more than one, much more than one? The answer is shocking: as many as

40 during each bullfight. Disembowelled dying and dead horses, the

intestines of horses and the blood of horses made battlefields of the

bullfighting arenas.

In these scenes of utter carnage such bullfighters

as Joselito, ('a classical purist,' according to Alexander

Fiske-Harrison) Belmonte and

Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, the subject of the poem by the poet and

dramatist Lorca, practised their art. Like Hemingway, the poet and

dramatist saw large numbers of these dead and dying horses but found

them not in the least important.

A pre-Peto film showing the slaughter of horses in the bullring during

this period: the horrifying scenes which Lorca and Hemingway witnessed

often, the horrifying scenes which took place in the bullfights of matadors

singled out for praise by Alexander Fiske-Harrison, Tristan Garel-Jones and

so many others.

A

contemporary film showing similar scenes of disembowelling, but without

the 'artistic purity' which for Lorca, Hemingway and others made such a

difference. Before the film can be viewed, it's necessary to sign in.

The fate of the picadors' horses in the bullring before

the protective mattress or 'peto' was adopted in 1929 is a subject of

far more than historical interest. It was revulsion against the

slaughter of the horses (not shared by Hemingway or Lorca) which led to the

adoption of the protective mattress. But this didn't end the suffering of

the horses. Revulsion against their suffering - and the suffering of the bull - is much

more widespread now than then. The revulsion which makes a return to conditions

before 1929 unthinkable makes it very likely that bullfighting will

eventually be abolished.

Bullfighting has surely reached its lengthy final phase.

'From 1914 to 1920 was bullfighting's Golden Age,' according to Alexander Fiske-Harrison's blog. In this estimation, he

more or less follows Hemingway, who ' placed the

Golden Age between 1913 and 1920. In this 'Golden Age' up to 40 horses were

slaughtered in each bullfight. Alexander Fiske-Harrison tries to balance the 'artistry' and

animal suffering at various places in his book

Into the Arena (I don't accept in the least his claims concerning the

artistry) and makes his own decision as to their relative importance - a

decision which is in stark contrast with my own ideas. I don't discuss the 'artistry' at all here, only the cost in animal

suffering, and not the suffering of the bulls (atrocious though it was, and is),

only the suffering of the horses.

As for the evidence, I make use of the book by Miriam Mandel

'Hemingway's The Dangerous Summer: The complete annotations.' Miriam Mandel

has more than enough knowledge of bullfighting and more than enough

enthusiasm for bullfighting to be considered an aficionado. This doesn't

affect the thoroughness or accuracy of the scholarship in the book, but it

does affect my attitude. The book is repulsive, horrible, but invaluable.

The figures given by Miriam Mandel apply to 'The Golden Age of Bullfighting'

and to a much, much longer period before 1929:

... many horses—sometimes as many as forty - were killed at each corrida.

[bullfight]'

A great deal of information is given about the rulings and regulations

governing the bullfight. The rulings and regulations which concern the

number of horses to be provided for each bullfight reflect

expectations about the numbers likely to

die at each bullfight. The book gives this information:

'In 1847, a local ruling

required that forty horses, inspected and approved by the authorities,

stand ready for use in each bullfight. The 1917 and 1923 Reglamentos

called for six horses per bull to be fought, with the added proviso that

the management provide as many additional horses as were necessary. Sometimes all the horses would be killed and replacements would be hastily

bought off cabbies and rushed into the ring.'

The addition of (!) to this last piece of information, about the

'replacements ... hastily bought off cabbies and rushed into the ring' would

be understandable but inadequate to the horror.

The scholarly information includes this: 'Perhaps the most important marker of change is

the Reglamento (taurine code), which evolved

significantly from its early version, drafted by Melchor Ordóñez in about

1847, to the increasingly detailed and prescriptive documents published

in 1917, 1923, 1930, and, post Hemingway, in 1962, 1992 and 1996.'

Whatever the number of horses killed in the ring

- fewer than twenty, or twenty, thirty or forty - the sight of the

horses' blood, the intestines of the disembowelled horses, the horses in

agony, the dead horses, the sights which didn't disturb Hemingway or Lorca,

the sights which Alexander Fiske-Harrison overlooked or didn't think too

important - these sights aren't going to

return to the contemporary bullfight.

Miriam Mandel writes, 'Occasionally one hears reactionary calls for the abolishment of the peto, but modern sensibilities would not allow a

return to the pre-peto

bullfight that Hemingway encountered when he first went to Spain.

The peto or

'protective mattress' for the picadors' horses 'was first used at a

Madrid novillada on 6 March 1927, and it was mandated by law on 18 June 1928.' After the peto was introduced, there was a vast decrease in the number of

horses disembowelled and the number of horses killed in the ring, but as I

explain in the next section, The horses, there are

still horses disembowelled in the ring - the horses of mounted bullfighters

('rejoneador') and the horses of picadors. The peto protects against

puncture wounds but not at all adequately against the weight of the bull

smashing into it and the peto disguises so many injuries. The

horses in the bullfighting ring are still treated with despicable cruelty.

It's true that 'modern sensibilities would not allow a return to the pre-peto

bullfight' but Miriam Mandel overlooks the obvious fact that modern

susceptibilities find unacceptable - repellent - the treatment of horses and

bulls in the contemporary bullring. The page gives abundant documentation of

this treatment. What was once accepted isn't accepted any longer, except by

the supporters and patrons of bullfighting. Many of these wouldn't object in

the least if forty horses died by disembowelling at every bullfight, but I'd

claim that although there's no such thing as certain moral progress, these

people have been left far behind by this particular moral advance.

When Alexander Fiske-Harrison described the years between 1914 and 1920

as bullfighting's 'Golden Age,' I doubt if he gave the least thought to any

other contemporaneous events. When humanity was undergoing the catastrophic

sufferings of the First World War, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 -

1919, which killed far more people than the First World War, somewhere

between 20 million and 40 million people in all, including vast numbers of

people in Spain (the term 'Spanish flu' is often used), was all this

outweighed by, compensated by, the Golden Age of bullfighting? Elementary

sensitivity should have led him to use a different term or to make his

discussion much more complex.

The bull

Before abolition in Catalonia: bull in the plaza 'La Monumental,'

Barcelona

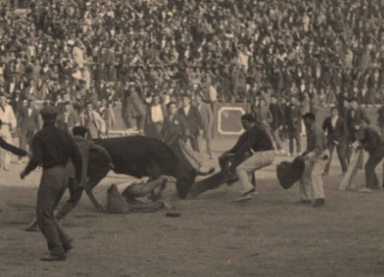

There are many, many images

and films available on the internet which show the course of a bullfight.

I think it's advisable to see some of these images and watch some of the films.

None of these films, none of the films distributed by convinced opponents

of the bullfight, show untypical 'atrocities,' incidents which are very rare.

The bull is never wounded and killed under controlled conditions. Whatever

the intention, the lance of the picador, the banderillas and the sword regularly

penetrate flesh not at all near the targetted area. The picador's horse may

be about to fall as the bull's massive weight charges into it, the lance may

sever an artery and blood pulses out. Hemingway mentions the fact that the

bull 'may be ruined by a banderillero nailing the banderillas into a wound

made by the picador, driving them in so deep that the shafts stick up straight.'

When blood pours out of the mouth and nose of the bull, which is often, the

sword has failed to cut the aorta (the heart is out of reach of the sword.)

When the bull is about

to be killed, it will already have had its back torn open by the lance of

the picador and will already have had its back lacerated repeatedly by the

barbed banderillas. By the time of the sword thrust supposed to kill the bull,

the bull will have two or three stab wounds inflicted by the picadors and

six stab wounds from the banderillas.

The sword often hits bone,

or goes deep into the animal but fails to kill. The bull, staggering, still

alive and conscious, with the sword embedded in its body - this is far more

common than an instantaneous death. A report by Tristan Wood in 'La

Divisa,' the journal of the 'Club Taurino' of London, on the bullfighter

Miguel Abellán: ' ... an excellent faena of serious toreo, only for its

impact to be dissipated by four swordthrusts.' The excellence and seriousness

found here are surely only an aesthete's response.

In the same set

of reports, on the bullfighter Morante de la Puebla: 'the swordwork

was very protracted.' Or, alternatively, the bull died a very slow death.

From the gruesome, matter of fact accounts of bullfights on the site 'La

Prensa San Diego'

http://laprensa-sandiego.org/archieve/october04-02/sherwood.htm

'Capetillo received a difficult first bull and encountered big troubles

at the supreme moment, requiring 12 entries with the sword.' 'Moment' is

very badly chosen. The writer is Lyn Sherwood.

Daniel Hannan, a Member of the

European Parliament and devoted aficionado: 'After the banderillas, as

the bull stood spurting fountains of blood ... ' there was 'a

miserable excuse for a sword-thrust into the bull’s flank.'

This shocking video

shows

the bullfighter Antoni Losada stabbing a bull with the 'killing sword' seven

times in the bullring at Saint-Gilles, France.

After the 'killing

sword' has been used to no effect, a different sword, the descabello, or a short knife,

the puntilla, is used to stab the spine, often repeatedly.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison saw a bull stabbed

three times with the 'killing sword' but still alive, and then stabbed

repeatedly with the descabello. According to the 'bullfighting critic'

of the newspaper 'El Mundo' who counted the stabbings, the bull was

stabbed in the spine seventeen times before it died. This experience had a

lasting effect on his girlfriend, 'her perspective on bullfights changed for

ever,' but Alexander Fiske-Harrison went on attending bullfights, went on to

kill a bull himself and opposes the abolition of bullfighting.

From my critical review

of A L Kennedy's On Bullfighting, quoting from the book. A L Kennedy is watching

a bullfight at the most prominent of all bullrings, Las Ventas in Madrid:

' At the kill, the young

man's sword hits bone, again and again and again while the silence presses

down against him. He tries for the descabello. Five blows later and the animal

finally falls.' The descabello, as the Glossary explains, is 'A heavy, straight

sword' used to sever the spine.

' 'I have already watched

Curro Romero refuse to have almost anything to do with his bull, never mind

its horns. (The severely critical response of a member of the audience to

a cowardly bull or a cowardly bullfighter.) He has killed his first with a

blade placed so poorly that its tip protruded from the bull's flank...As the

animal coughed up blood, staring, bemused, ['bemused?'] at each new flux the

peones tried a rueda de peones to make the blade move in the bull's body and

sever anything, anything at all that might be quickly fatal, but in the end

the bull was finally, messily finished after three descabellos.'

'The suffering of the

bull 'left, staggering and urinating helplessly, almost too weak to face the

muleta' wasn't ended by a painless and instantaneous death: 'Contreras...misses

the kill...Contreras tries again, hooking out the first sword with a new one

...Contreras finally gives the descabello.' So, the sword is embedded in the

animal, the sword is pulled out and thrust into the animal yet again, but

it's still very much alive, the ungrateful creature. The descabello is hard

at work in this book. People who have the illusion that the 'moment of truth'

amounts to a single sword-thrust and the immediate death of the bull are disabused

of the notion here. More often, the moment of truth is hacking at the spine

with the descabello.'

The cutting off of the

bull's ears before it's dead - this is less common. What humanitarians these

people are! They generally wait until the bull is dead before cutting off

the ears! Not always, though. On occasion, they are impatient for some reason

and can't wait.

The life and death of

the bull are sharply contrasted. The bulls are treated humanely until they

arrive at the bull-ring, but their sufferings may begin even before the picador

thrusts his lance into them. Sometimes, thick needles have been pushed into

the bull's testicles before they enter the ring.This practice is said to subdue

any bull, and no wonder.

The claim is made by bullfighting

apologists that the bull that dies in the bullring is 'lucky.' The claim is

made that these bulls have a far better life and a longer life (although not

much longer) than the bulls reared for beef, kept in factory farms and slaughtered

at a younger age. The claim is made that when bulls are 'tested' for their

fighting qualities - the 'tienta' - the bulls which go to the bull ring are

much more fortunate than the ones that fail, that will be slaughtered for

beef.

Pigs and chickens, both

the chickens reared for meat and laying chickens, are very often kept in factory

farms but this isn't true of beef cattle in most cases. I can claim to have

an exhaustive knowledge of the subject - I've opposed factory farming for

a very long time. Animals other than pigs and chickens have been kept in factory

farms to a lesser extent, or attempts are being made to factory farm them.

In this country, there are planning applications - which are being strenuously

resisted - to adopt the hideous 'zero-grazing' system for dairy cows in massive

factory farm complexes.

But generally, beef cattle

have just as good a life as fighting bulls, grazing in fields. It's true that

their life is generally shorter. Fighting bulls are at least four years old

when they enter the bullring for the regular corrida, but the 'novillos,'

the bulls fought by the apprentice matadors or 'novilleros' are closer in

age to beef cattle. When Frank Evans, the British bullfighter, came out of

retirement to fight - and kill - a bull, the bull was just two years old.

The picture I have is poignant, not for its image of the bullfighter fighting

long after most bullfighters have retired but for the bull, not at all a good-looking

bull, much slighter than a four year old bull, of course - to put this animal

to the sword needed even more callousness than usual, I feel.

But the arguments of bullfighting

apologists which refer to factory farming and the age of slaughter are surely

cynical, opportunistic. There's no evidence at all that most of these people

are concerned in the least about factory farming and the slaughter of animals.

'Thought

experiments' are often used in ethical discussion. They can be used to support

or oppose an ethical argument very graphically. In the case of the 'lucky'

fighting bull, these analogies suggest themselves. The death of gladiators

in the Roman arenas is widely recognized as a blot on Roman civilization -

indefensible. The Romans might have developed a system according to which

all the gladiators were made up of men condemned to death, volunteering to

fight instead of being executed. They had the chance of living for longer,

and perhaps much longer. Even if they were beaten in combat, the crowd might

spare their lives. What if a contemporary jurisdiction which often executes,

such as Texas, proposed to allow condemned men the same chance of living for

longer and by similar means?

It

would be unthinkable, of course. There's massive opposition to the infliction

of death in public. In the history of the death penalty, the trend has been

for executions to be public, then not seen by the public, within the confines

of a prison, before being abolished altogether. Similarly, if an animal is

being slaughtered, then to make a public exhibition of the slaughter is felt

to be degrading.

Human responsibility towards

domesticated animals, and standards for keeping domesticated animals should

include as a bare minimum (1) humane treatment whilst the animal is reared

and (2) a humane death. These should be regarded as essential, fundamental

principles of animal welfare in a modern civilization. Battery chickens are

denied (1). They have the benefit of (2) almost always, but not invariably.

The bull has the benefit of (1) but not (2). Beef cattle generally have the

benefit of (1) and (2). No matter how well treated it may have been before

arriving in the bullring, the death of the bull, more often than not far from

instantaneous, preceded by injuries which are likely to be painful or agonizing,

is an act of disgusting cruelty that shames Spain, France, Mexico, Peru, Colombia,

Venezuela and Ecuador.

The

courage of the bullfighters. Mind Mush: Paul Staines, Guido Fawkes.

Alex Honnold on Liberty Cap, Yosemite, climbing without a climbing rope

or any other form of protection - free climbing.

The North Face of the Eiger (Acknowledgments: flickr)

NEW: The illusions and distortions of Paul Staines, founder of the blog

'Guido Fawkes.'

Here, I concentrate on some of his weaknesses: his support for bullfighting,

his support for the reintroduction of the death penalty for some offences,

in an initiative of 2011, the stupidity of some of his attitudes to safety.

With this section, I launch a very small campaign against Paul Staines.

Anything bigger would be a waste of my time and a waste of space. Paul

Staines himself isn't a complete waste of space, far from it. His blog

'Guido Fawkes' has many strengths. I intend to include a profile of

his site on this site. There are already profiles in depth of other mainly

political sites with extensive comments sections,

https://www.linkagenet.com/themes/gbnews4.htm

'GB News,

other anti-woke sites and other issues'

and a long review of Harry's Place on my page on

The Culture Industry

Below, some ridiculous Mind Mush from the Guido Fawkes page.

I can also show that it's loathsome - the mention of 'safety nazis,' gross

misuse of the word 'Nazi, which should be reserved for attitudes and actions

which led to extermination or results of similar seriousness. Does Paul

Stains drive a vehicle? I don't know. If he does, does he wear a seat belt?

Climbers, discussed below at length, sometimes wear a safety helmet,

sometimes not. For dangerous Alpine and Himalayan climbs, they'll always

wear a safety helmet. For bouldering and sometimes for very short short climbs, climbers dispense with a climbing rope but virtually all climbers use a climbing rope

for longer climbs. I discuss the exceptions here, free climbers, and one

free climber in

particular, Alex Honnold.

This is Paul Staines, 'Guido:'

https://order-order.com/2009/07/10/remembering-running-with-the-bulls/

Guido was rummaging in the attic last weekend and found his old blood

spattered pañuelo and faja (the

sash and neckerchief worn by the runners in Pamplona). This week is

the festival of San Fermin and the news this morning

that a runner was gored to death made Guido feel a bit misty-eyed. The

second week of July every year for a decade from Guido’s mid-twenties to his

mid-thirties would see him in Pamplona doing the run, usually with his

brother or friends. As a veteran of some 30 runs it is fair to

say it was an adrenaline addiction – partying all night and running for your

life in the morning. Hangovers clear fast

when you hear the rocket fired that signals the release of the bulls.

In a sterile world of safety belts, safety helmets and safety nazis, the Pamplona bull run is a glorious celebration of the

irrational side of the human spirit. They say that an old man who has

not risked his life for his country feels less of a man than an old soldier,

so to have never risked your life must be far worse. To risk your life

makes you feel more alive.

Guido prays the cloak of San Fermin will protect los

corredores who will run this week

and wishes he was with them. May God have

mercy on the soul of the corredor who so vicerally [he means: 'viscerally']

lost his life: Saludo!

To appreciate just how ridiculous and overblown this is, we need to look

at it with the cold gaze of a statistician. ''Pamplona bull run deaths are rare, but since 1910 when record-keeping

began, 16 people have died.' This is according to the page

Runningofthebulls What's the point of the word 'but' here? 16

fatalities in this time span is rare.

Please see also in this column, Pamplona: a proposal.

My page on The death penalty has the

heading, 'The death penalty: against, but not always.' The exceptions relate

mainly to the past. I take the view that far more Nazi war criminals should

have been executed after the Second World War. I give my reasons on

the death penalty page.

In this section, I discuss the risks of

mountaineering and some forms of rock climbing, the risks of battle and the

risks of bullfighting. I point out that the risks of bullfighting are

grossly and grotesquely exaggerated by bullfighters and defenders of

bullfighting.

I begin with mountaineering. I was a cross-country skier and I've

used cross-country skis in the Alps for downhill skiing. Steve Barnett's

book 'Cross-Country Downhill,' mainly about skiing in the Canadian and

American North-West, is a fine introduction to its compelling attractions,

but my own skiing was much more limited. My rock climbing career, on the

other hand, was very brief. The experience of dislocating a shoulder twelve

times - not on a rock face - was one of the things that convinced me that I

wasn't well suited to rock climbing.

Of course, anyone who takes up mountaineering and climbing in other

settings will need to consider very carefully the risks. Many of them are

avoidable, but not all. .

Edward Whymper wrote in 'Scrambles Amongst the Alps,'

“Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought

without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness

of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the

beginning think what may be the end.”

Edward Whymper is best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in

1865. During the descent, four members of the climbing party were killed.

Climbers almost always use modern methods of protection, which include

not just climbing ropes but many other sophisticated pieces of equipment.

Free climbers don't. The best known free climber is Alex Honnold, shown

above. If free climbers fall, almost always they die.

If we compare bullfighting

and high-altitude mountaineering, then high altitude mountaineering is far

more dangerous than bullfighting, as well as incomparably more interesting,

more demanding, and, if you like, more 'noble.' Now, with modern equipment

and techniques, it's far less dangerous than it used to be but the fatality

rate on high mountains still averages something like 5%. That is, one in twenty

of the mountaineers on an expedition will not return. Some mountains have

a much higher fatality rate. K2, the second highest mountain in the world,

has claimed more than one death for every four successful ascents. Annapurna

is even more deadly. Compare the number of fatalities for the tiny

number of mountaineers attempting to climb just one Himalayan peak,

Annapurna 1, which can easily be confirmed (Unlike bullfighting,

Himalayan mountaineering has immensely detailed sources of statistics, such

as

himalayandatabase.com): 58 fatalities between the successful summit attempt in

1950 and 2007, a total of only 153 summit attempts. (And whereas injured

bullfighters have speedy access to modern medical care, the case is very

different for injured high-altitude mountaineers. The frostbitten fingers

and toes of the two climbers who made the first ascent of Annapurna 1 became

gangrenous and were amputated on the mountain without anaesthetic.) To

climb Annapurna (a deadly mountain, but not the most dangerous peak) or

another very high mountain - or many much lower mountains, for that matter - just once involves a far higher risk of death

than a bullfighter faces in an entire bullfighting 'career.'

Reinhold Messner

describes the first ascent by the French climbers Herzog and Lachenal,

which was also the first ascent of any mountain over 8 000 metres high. Herzog

was caught in an avalanche, knocked unconscious, was suffering from frostbite.

Along with others in the party, he waded through deep snow back to Advanced

Base Camp, in an epic of endurance. To climb K2 or Annapurna or another very

high mountain just once involves a far, far higher risk of death than a bullfighter

faces in an entire bullfighting 'career.'

France has every reason

to feel pride in these and so many other mountaineers, just as France has

every reason to feel shame about its bullfighters.

Injuries to mountaineers

occur not only as a result of falling but from a range of other causes, such

as rock fall and avalanches - the snow which makes up the avalanche may resemble

the consistency of concrete rather than anything soft and fluffy, capable

of causing crushing injuries and multiple fractures.

On high mountains, the

ferocity of the winds and blizzards often make a rescue from outside impossible

until it is too late. Rescue facilities are well organized in the Alps, not

at all in the Himalayas and the Andes. Even in the Alps, bad weather can delay

rescue for days, or rescue may be impossible. For the mountaineer, safety

and medical help are generally far, far away.

An injured bullfighter,

on the other hand, can be taken from the ring almost immediately to the bull-ring

clinic and then to a main hospital. For this reason, injuries in the bull-ring

are almost always non-fatal. And on the other side of the barrera, the low

barrier surrounding the bull-ring, lies safety. At all times, safety is so

near. Another advantage: a bull-fighter is in the position of danger for such

a short time. A mountaineer may be in an area of acute danger for days or

weeks. The dangers are not just the ones that result from errors, which are

completely understandable, given the enormous demands which the mountains

make on the human mind and body. There are also 'objective' dangers, from

the stonefalls that occur regularly in the mountains, avalanches, crevasses,

other dangers that result from the unpredictability and instability of snow.

When, on the mountain

called 'The Ogre,' Doug Scott broke both his legs, safety was far away. The

party was caught by a storm and it took six days, five of them without food,

to descend. Chris Bonington, also in the party, broke ribs during the descent.

Another,

now famous, story of magnificent bravery and endurance in the mountains is

that of Joe Simpson, which he recounts in his book 'Touching the Void' (available

in French, Spanish and many other languages). In 1985, he and Simon Yates

set out to climb the remote west face of the Siula Grande in the Peruvian

Andes. It was 1985 and the men were young, fit, skilled climbers. The ascent

was successful, after they had climbed for over three days. But then Joe Simpson

fell, and broke his leg badly. There was no hope of rescue for them. They

had to descend without any help. Yates was lowering Simpson on the rope but

lowered him into a hidden crevasse. He couldn't hold him and was forced to

cut the rope. Simpson wasn't killed by the fall, He managed to drag himself

out and drag himself down the mountain, dehydrated and injured, until, at

last, he reached base camp.

The Wikipedia entry for the

Eiger gives valuable information about the ascents of the infamous North

face, shown in the image at the beginning of this section, including solo

ascents, the injuries, fatalities, rescues, successful and unsuccessful,

stories of courage and endurance which put bullfighting in its place. Since

1935, at least sixty-four climbers have been killed whilst climbing it -

compared with the 52 bullfighters who have been killed in the ring in a

period of over 300 years since 1700. Taking into account the number of

climbers making the attempt, tiny compared with the number of bullfighters

fighting in that period, climbing on the North face is far more dangerous.

The Wikipedia information on one summit attempt, made

only a few years after Lorca made his fatuous remark about bullfighting

being 'the last serious thing in the world.' This attempt on the Eiger, like

all the others before and since, was a serious matter by any reckoning. It

also underlines the closeness of safety in the bullring, the availability

of prompt medical care in the bullring, the lack of these in the mountains,

and the fact that it's not only bullfighters who face injury.

'The next year [1936] ten young climbers from Austria and Germany

came to Grindelwald and camped at the foot of the mountain. Before their

attempts started, one of them was killed during a training climb, and the

weather was so bad during that summer that after waiting for a change and

seeing none on the way, several members of the party gave up. Of the four

that remained, two were Bavarians, Andreas Hinterstoisser and

Toni Kurz, the youngest of the party, and two were Austrians, Willy

Angerer and Edi Rainer. When the weather improved they made a preliminary

exploration of the lowest part of the face.

Hinterstoisser fell 37 metres

(121 ft) but was not injured. A few days later the four men finally began

the ascent of the face. They climbed quickly, but on the next day, after

their first bivouac, the weather changed; clouds came down and hid the group

to the observers. They did not resume the climb until the following day,

when, during a break, the party was seen descending, but the climbers could

only be watched intermittently from the ground. The group had no choice but

to retreat since Angerer suffered some serious injuries as a result of

falling rock. The party became stuck on the face when they could not recross

the difficult Hinterstoisser Traverse where they had taken the rope

they first used to climb. The weather then deteriorated for two days. They

were ultimately swept away by an avalanche, which only Kurz survived,

hanging on a rope. Three guides started on an extremely perilous rescue.

They failed to reach him but came within shouting distance and learned what

had happened. Kurz explained the fate of his companions: one had fallen down

the face, another was frozen above him, the third had fractured his skull in

falling, and was hanging dead on the rope.'

In the morning the three guides came back, traversing across the face

from a hole near the Eigerwand station and risking their lives under

incessant avalanches. Toni Kurz was still alive but almost helpless, with

one hand and one arm completely frostbitten. Kurz hauled himself off the

cliff after cutting loose the rope that bound him to his dead teammate below

and climbed back on the face. The guides were not able to pass an

unclimbable overhang that separated them from Kurz. They managed to give him

a rope long enough to reach them by tying two ropes together. While

descending, Kurz could not get the knot to pass through his carabiner. He

tried for hours to reach his rescuers who were only a few metres below him.

Then he began to lose consciousness. One of the guides, climbing on

another's shoulders, was able to touch the tip of Kurz's crampons with his

ice-axe but could not reach higher. Kurz was unable to descend farther and,

completely exhausted, died slowly.

The intensity of the dangers

in the high mountains, the fact that these dangers are so protracted, the

beauty of this hostile environment - these and other factors have their effect

on human consciousness. Anyone who has read enough books about mountaineering

and by mountaineers and enough books about bullfighting and by bullfighters

to be able to compare the two will surely be convinced that the states of

consciousness revealed in mountaineering literature are incomparably richer,

deeper and more complex.

What are the achievements

of bull-fighters to be compared with the achievements of mountaineers? What

bravery has been shown in the bull-rings of Arles, Nîmes, Madrid, Seville,

Valencia, Granada, Mexico City, all the bull-rings of the bullfighting world,

that could possibly be compared with the bravery shown on Annapurna, Everest,

the Matterhorn, the North Face of the Eiger and the other peaks? The summit

may be reached or not, but mountaineers have every reason for pride. Bullfighters

are obviously very proud of those bleeding, still-warm ears that have been

cut from the bull as a mark of their 'achievement.' Revulsion is the only

proper, civilized response.

Of all risky activities,

none has anything like the bullfighters' highly developed Mythology of Death.

Mountaineers tend to be self-effacing and reticent, at least in talking about

the dangers. They are acknowledged and mentioned, but there's none of the

decadent boasting indulged in by bullfighters, and so for other people who

take part in risky activities. During the Winter Olympics at Vancouver,

2010, one of the competitors in the luge event, one of the men and women who

hurtle down the ice at terrifying speeds, was killed. The competitors showed

restraint and dignity and hurtled down the ice in their turn, without

histrionics. The biography of the Spanish bullfighter of a previous

generation, El Cordobes, was entitled, 'Or I'll dress you in mourning,' referring

to his boast that he would make good in bullfighting or die in the attempt.

(Like the vast majority of bullfighters, he didn't die in the attempt.) The book

- one I haven't, to be fair, read from cover to cover, only in large extracts

- is astonishing. I think particularly of the effusive bullring chaplain

holding up a religious medal when it seemed that El Cordobes' histrionic

heroics were becoming particularly risky.

The English

bullfighter Frank Evans has written about the women who are attracted to him

because of the supposedly glamorous danger he faces.

A L Kennedy makes a grotesque

comparison, in connection with the bullfighter 'El Juli,' who, rumours have

it, 'will soon attempt to face seven bulls ... within the course of one day...

At this level, the life of the matador must be governed by the same dark mathematics

which calculates a soldier's ability to tolerate combat: so many months in

a tour of duty, so many missions flown, and mental change, mental trauma,

becomes a statistical inevitability. But in the corrida, the matador is not

exposed to physical and emotional damage by duty, or conscription - he is

a volunteer, a true believer, a lover with his love.' This comes from her

book 'On Bullfighting.' I note in my review of the book, ' ... ten years after

she wrote about him and his likely demise, El Juli is still with us, still

very much alive, despite the dark mathematics.'

John McCormick gives the same argument in the morass of

ignorance and falsification that makes up a significant part of 'Bullfighting: art, technique and

Spanish society.' He writes of the bullfighter, 'Just as the suit of lights

marks him off in the plaza from the run of men, so in his own mind he is

marked off always ... The closest thing to it I knew was fear of combat, but

that was different too, because there was always the comforting sense of

having been coerced.

The difference in toreo lies in the element of choice.

Only the toreo chooses freely to risk wounds or death.'

Not true of the volunteers from this country and others who went to fight

in the Spanish civil war, such as George Orwell, who was shot in the throat.

The merchant seamen who served on the ships bringing supplies to this

country during the Second World War were all volunteers. Many of the

particularly dangerous missions undertaken in the Second World War were

undertaken by volunteers. All those members of the armed forces from

Northern Ireland who fought against the Nazis were volunteers - there was no

conscription in the province during the war - and obviously all those from

the Irish Republic who joined the British armed forces to fight

against Nazism, around 38 000 in number. The soldiers of this country who

fought in The First World War in 1914 and 1915 were volunteers. Conscription

wasn't introduced until 1915. This is an incomplete list, which could be

vastly extended, of evidence from before the publication of the book in

1967. Events since would provide further contrary evidence. For example, the

soldiers from this country and others who fight against the Taliban in

Afghanistan. The men and women who work in bomb disposal, amongst other

things making it safe for villagers to return to their villages, are all

volunteers. And evidence from other activities before and after he

wrote, for example, the mountaineers who risk death in the mountains,

practitioners of high risk sports in general, are obviously all volunteers.

Again, obviously an incomplete list.

Some opponents of the

bull-fight refer to the matador as a coward. This is a clear instance of what

I refer to as alignment, which involves a distortion of reality.

It's also an instance of alignment to claim that Picasso cannot have been

a great artist because he was so devoted to the bullfight. Picasso's work

leaves me cold, including the overrated painting 'Guernica,' but I recognize

his importance as an innovator, his secure place in the history of artistic

modernism. (All the same, when I think of his devotion to the bullfight rather

than his artistic importance, then to me he's 'Pablo Prickarsehole.')

The mistake of rejecting

achievement because of an objection to the person's personality or one aspect

of the work, is discussed in the case of another Spanish artist, Salvador

Dali, by George Orwell ('Benefit of Clergy: some notes on Salvador Dali.')

Similarly, to decide that Descartes cannot have been a great philosopher because

of his notorious view that animals are automata and cannot feel. Descartes'

position as one of the great philosophers is beyond dispute. His 'Meditations'

is one of the most attractive works in all philosophy, and certainly one of

the greatest works of rationalist philosophy.

To return to the bullfighters,

their courage surely can't be in doubt. If fatalities in the bullring are

rare, gorings and other injuries are not. Nobody who was a coward would choose

to occupy the same space as a half-tonne bull with sharp horns, but I think

I've established that their courage is strictly limited.

A related issue: the ethics

of climbing and the ethics of bullfighting. 'The ethics of bullfighting' here

has a very narrow meaning: whether or not the bull is tampered with to make

the work of the bullfighters much less dangerous. Better to call it 'code.'

The word 'ethics' shouldn't be used in connection with bullfighting. The shaving

of the bull's horns is one notorious practice that makes a bull far less dangerous

but is commonly practised. There are others. Stanley

Conrad who runs what has been described as the 'best' (pro-) bullfighting

Web site in the world in English, admits this, in a review of A L Kennedy's

'On Bullfighting:' 'the critical issues plaguing the present

day corrida - weakened taurine bloodlines, horn shaving and other pre-corrida

attacks on the central creatures' integrity...'

Another critical issue plaguing the present day corrida is

cited in the routine and otherwise uncritical book 'Bullfight' by

Garry Marvin, a social anthropologist, which includes information about one

practice which I can't confirm from other sources. If true, it reflects the

tawdry dishonesty and corruption of the relationship between bullfighters

and journalists in Spain. He writes,

'In whatever novillada or corrida he is performing, it is important for

the matador to have preparado la prensa (literally, 'prepared the press',

meaning to have paid a certain amount of money to the reporters and

photographers who will cover the event), because the reports of a

performance can have a considerable influence on the chances of further

contracts. If not sufficiently 'prepared', the press can damn a good

performance with faint praise or can concentrate on the odd bad moments

rather than on the overall performance. If well 'prepared' they can do

exactly the reverse and can find good things to say even though the matador

might have been booed from the plaza.' The same novillero who had the

problem with the festival performed extremely well on two afternoons in a

series of novilladas in a town near Valencia. He paid as much as he could to

the local newspaper critic, who was also a correspondent for a national

magazine dedicated to the corrida. The amount paid was obviously not enough,

and he received a few cursory lines in the report. Other novilleros who had

not done as well but who had obviously given more money received much more

coverage, including several flattering photographs.'

The book is described by the publisher as one which 'explains how and why

men risk their lives to perform with and kill wild bulls as part of a public

celebration ...' The usual ignorant or shameless overestimation of the

dangers to life which I discuss on this page.

Opponents of bullfighting

are often pessimistic - how to win a victory against forces seemingly so powerful

and entrenched? They should remember, though, that they are opposing something

which is diseased.

Breaches of climbing ethics

make the mountain easier to ascend, with less danger. They include resting

in the rope rather than using the rope purely to arrest a fall, in climbs

where artificial aids aren't permitted. Climbing ethics are almost always

observed, the 'bullfighting code' very often flouted. Climbers who would like

to climb a particularly dangerous rock face don't bring along explosives to

make the rock face less difficult and dangerous, but in bullfighting, the

most devious practices are common. And the bullfighters, not the climbers,

are the ones who will boast of the dangers, of how, in the case of male bullfighters,

the vast majority, the glamour of danger makes them attractive to women ...

The 'courage' of bullfighters

in the past was the means - the morally obnoxious means - by which a few individuals

could escape poverty and deprivation. As the bullfight apologist Michael Kennedy

acknowledges in 'Andalucia,' the growth of prosperity makes individuals less

and less keen to take risks in the bullring. The amounts that can be earned

are enormous. A bullfighter may earn more than most footballers in Spain. The

financial rewards of climbing are far less - for the vast majority of climbers

nothing whatsoever.

The people who run with

the bulls at the San Fermin Festival in Pamplona (and similar events) run a

risk of injury but most of the injuries are minor. The most common injury is

contusion due to falling. There have been fatalities in the bull-run: 15 fatalities in the last 100 years. Given the large

numbers of people who take part, this isn't very many. They include someone

suffocated by a pile-up of people and someone who incited a bull to charge him

by brandishing his coat.

The attempt to claim excellence

for bullfighting stumbles upon the fact that two categories essential for

these claims, physical courage and artistic achievement, are also categories

where humanity's achievements are stratospherically high.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison

lets slip in his book 'Into the Arena' the information that between 1992 and

the publication of his book in 2002, no bullfighters were killed in the ring

in Spain. In his blog, he gives a figure for the number of

professional bullfighters killed in the last three hundred years: 533. This is

one of the lists he refers to, the annotated list of deaths of matadors

since 1700:

http://www.fiestabrava.es/pdfs/MVT-1.pdf

This document, like

the others, omits context and comparison. For example, in 1971, José

Mata García died as a result of bullfighting injuries, but would probably

have survived if medical facilities at the ring had not been very poor. In

the same year, two Spanish matadors were killed in car accidents (a

Venezualan matador was killed in a car accident as well.)

Between 1863 and

1869, no deaths are recorded for matadors. During the American Civil War in

just one prison (Salisbury, North Carolina) during a four month period (October 1864 - February 1865) 3,708 prisoners died out of

a total of about 11 000. (Information from the 'Civil War Gazette.') This is

about a 33% mortality rate. If a similar mortality rate applied to

bullfighting, then in one single bullfighting season in Spain there would be

markedly more bullfighters killed than have been killed in three centuries

of bullfighting.

Or consider this as context for the death of 533

bullfighters in a period of over 300 years: Italian soldiers

facing soldiers of the Austrian-Hungarian army. On December 13, 1916

(later known as 'White Friday') 10,000 soldiers were killed in

avalanches.

Essential background for bullfighting mortality

statistics is the frequent recklessness of bullfighters. In the Anti-blog, I

refer to Padilla, injured but not killed, who head-butted a bull, obviously

very near to the horns, twice. Padilla lost an eye as a result, but in the

same year in which more bullfighters were killed in car accidents than in

the ring, 1971, a bullfighter lost an eye in a car accident.

The pro-bullfighting Website carrionmundotoreo.com has a

page on bullfighting risks written by Michael Cammarata, which includes

this: ' ... toreros are not inherently at risk for many health

conditions. Their lives may be complicated by injuries, but death by the

bull’s horns is rare, they are unbelievably resilient, and healthcare has

improved to the point that nearly all consequences or mishaps are

manageable.' Penicillin transformed bullfighting. Before its introduction,

accidents in the bullring, like accidents on the farm, were far more likely

to be fatal.

'In 1997, the Spanish government issued the first Royal

Decree significantly pertaining to "sanitary installations and

medico-surgical services in taurine spectacles" (Real Decreto de Oct. 31,

1997).' The regulation outlines the facilities which must be available:

'All infirmaries are expected to have basic amenities,

including sufficient lights, ventilation, generators for back-up energy

supplies, and a communications system. Mobile infirmaries should have a

minimum of two rooms; one for examination and another for surgical

intervention; however, the standards for fixed infirmaries are higher. A

bathroom, recovery room, and sterilization and cleaning room are also

necessary. The regulation continues to outline a list of necessary supplies,

such as central surgical lamps, tables, anesthesia machines, resuscitation

machines with laryngoscopes, intubation tubes, suction, and a cardiac and

defibrillator monitor. The responsibility for such materials lies in the

hands of the chief surgeon of the plaza.... events with picadors require the following staff: a chief

surgeon, an assisting physician with a surgical license, another physician

of any type, an anesthesiologist, a nurse, and an auxiliary person. Events

without picadors such as novilladas without picadors, sueltas de vacas, and

comic taurine events require a chief surgeon, a physician, a nurse, and

auxiliary person. Therefore, the difference is in the assistant surgeon and

the anesthesiologist. A plaza de toros has ambulances on site for emergency

transports from the plaza to the nearest hospital, during which at least a

nurse and physician must be on board the vehicle.

Fatalities to bullfighters may be very rare, but

fatalities to the horses used in bullrings don't seem to be nearly so rare -

but I haven't been able to find any statistics whatsoever. This

surprises me not at all. The bullfighting world seems to consider the

welfare of horses completely unimportant. When I found

bullfightingNews.com, this news piece was on the Home page, headed 'Diego