Multi-functionality isn't an original concept - it's widely cited and widely practised - but it's the new applications of the concept which require the new insights and breakthroughs. Multi-functionality is one of the important concepts in permaculture - although I don't accept all its concepts by any means. The book 'Permaculture in a nutshell' by Patrick Whitefield is an excellent introduction to Permaculture. He states 'every plant, animal or structure should have many functions.' I would add 'if at all possible,' add the qualification that they may only serve one function well, the others not nearly so well, and add tools and equipment to the list.

It's not always possible for things, including living things, to serve many functions without any serious disadvantages. I'd suggest that when old carpets and car tyres are used in allotments, their new functions are so different from their original function that they're not adapted to carry out the new function without serious disadvantages. Carpets, for example, are heavy and difficult to move, react badly to being soaked with water and will eventually present problems of disposal (except for ones made of natural fibres, which can be composted, with care).

I would extend the biological concept of adaptation to include adaptation of structures, tools and equipment. A plank of wood isn't adapted to one use. It's very versatile in its possible uses. Most other things tend to be not nearly so versatile.

Sometimes, it's best if one thing doesn't have more than one function. In various places in this site, I give my opinion that although plastic isn't the best material for composters and the boards surrounding beds, it is the best material for water butts. In water butts, one structure, the plastic, is called upon to carry out many functions - a leak-proof container for the water, giving shape to the container, resisting the forces which the water applies. To carry out all these functions needs a fairly thick plastic wall, and I think it's important to reduce the use of plastic to a minimum. Is there any way of reducing it? Obviously, there is.

The first of these functions, the leak-proof container for water, can be carried out perfectly well by a thin sheet of plastic, as is the case with the bags in which wine is sometimes sold. In this case, the shape and the ability to resist forces are provided by the cardboard box which encloses the plastic bag. A water butt which minimized the use of plastic - which minimized the use of a non-renewable resource - would consist of the inner plastic container, fairly thin wooden sides, to give shape, and two or three metal bands, to resist the forces which the water applies: a separation of structures and a separation of functions.

I use this structure-function model, extending structure to include pieces of equipment. In a one-many design one structure has many functions. For example, a single board has the functions of neatly separating the bed from the path, securing fleece, securing protective netting, acting as a temporary path, and so on. A single image can convey information but can also have a navigation function - clicking on it takes the user to the top of the page.In a one-one design one structure has one function - the function it can carry out efficiently. The plastic inner in a water butt (not commercially available as yet) has the function of acting as a leak-proof container for the water. It doesn't have the strength to carry out other functions, such as giving shape or resisting the lateral forces of the water - these are carried out by wooden structures and the metal bands.

Another example of multiple-functionality (which includes 2-functionality or dual functionality.) Joy Larkcom's 'Creative Vegetable Gardening' (not a very good title, I think, for a very good book) is for all people with a very strong interest in vegetables (but she calls them 'vegetable lovers') who would like 'a vegetable garden that is beautiful and productive.' Amongst other things, Joy Larkcom considers the visual interest of edible plants.

The fact has to be faced that some plants with an intense or interesting taste have a dull and uninteresting appearance, but others do have visual impact. She mentions the well-known fact that the runner bean plant (Phaseolus coccineus) was introduced into Europe for its ornamental strengths.

She mentions the attractive flowers of some varieties of potato plants, so attractive that they can act as dual-purpose plants, to be grown for their visual interest as well as for eating:

These flowers 'can be subtle shades of mauve, purple-blue and pink, or else creamy white, contrasted in a delightful way with bright yellow centres.'

Flowers - the wrong appearance for garden design?

In the previous section, I discussed some disadvantages when things aren't used for their original purpose, when carpets are used for light starvation of weeds for example, or car tyres are used as plant containers. At the end of this section, I include an extract from my page on concrete poetry - poetry which uses letters and punctuation marks to create visual effects. The title is 'Letters: the wrong shape?' I write, 'Using letters and other objects of written communication for visual design is problematic. Are they really multi-functional, capable of being one-many design elements?'

In garden design, flowers too are used as multi-function elements. Their central function is not necessarily to attract insects for pollination, by means of bright colours and in other ways, but in the case of both insect pollinated and wind pollinated flowers, their central function is reproductive. That's not to claim that every aspect of the appearance of a flower is to do with reproduction.

In the case of ornamental gardening (and gardening for sensousness or gardening for beauty and gardening to promote harmonious feelings), how well adapted are flowers for the desired end?

Gardeners who use colour theory in designing a garden generally try to plant flowers and encourage flowers which seem to be in accordance with colour theory and which suit their purpose, which may be clashing of colours as well as colour harmony, but the flowers they choose may not be too cooperative.

Green is a hue whose connotations include restfulness, calm, freshness, renewal. Red is a hue whose connotations include passion, sexiness, festivity, with negative connotations which include violence.

Again and again, green crops up, and may not associate too well with flower colour. If the desired effect is a mass showing of red, a particular shade of red, the presence of green stems and leaves is likely to make the effect less intense, to be a distraction, in fact.

Some very useful categorizations of present-day gardens come from fields other than gardening, such as 'Renaissance architecture' and 'Baroque architecture.' In 'Renaissance and Baroque, Heinrich Wölfflin writes (Chapter II, 'The Grand Style') in general terms, not at all at his best, before addressing in wonderful detail the techniques by which the architects and builders achieved such very different effects:

'Renaissance art is the art of calm and beauty. The beauty it offers has a liberating influence, and we apprehend it as a general sense of well-being and a uniform enhancement of vitality. Its creations are perfect: they reveal nothing forced or inhibited, uneasy or agitated.

...

'Baroque aims at a different effect. It wants to carry us away with the force of its impact, immediate and overwhelming. It gives us not a generally enhanced vitality, but excitement, ecstasy, intoxication.'

Is the present-day gardener to make use of red roses, then, or any other plants with red petals (or sepals), given that the inescapable green will interfere with the red, leading to loss of intensity in a present day 'baroque garden,' and the inescapable red may lead to too much intensity in a present day 'renaissance garden?'

Letters: the wrong shape?

What about letters and other objects of written communication? Their primary function is semantic, to convey information and things that are more than information in the distinctive setting of written communication. Using letters and other objects of written communication for visual design is problematic. Are they really multi-functional, capable of being one-many design elements?

The lines which are used in drawing are capable of almost endless variety in their length, shape, emphasis and placing. The lines which are letters and other objects of written communication are subject to severe {restriction}. The particular shapes of so many letters aren't particularly suited to general design. Many of them have projections, are bulbous. The shapes can be subjected to {modification} so that they are more suitable for the purposes of a particular design, but obviously the {modification} is subject to {restriction}. After a certain point, the letter becomes unrecognizable as the letter.

Some letters are well adapted to general purpose use as 'design marks' such as 'l' in the font Verdana. Sans-serif fonts are far better adapted than Serif fonts, but no matter what font is used, many other letters are far less suited as 'design marks,' such as a, b, d, e, g, h, k, y, z.

'z' is made up, in this font, of two horizontals and a diagonal. So, at the micro-level of this element, we have the visual statement of two horizontals and a diagonal. This may or may not be well integrated with the macro-level: let's say, a design which makes particular use of verticals. Similarly, 'p' and 'b' in Verdana are both made up of a radial component, approximately circular, and a straight-line vertical, not very prominent in this font. Again, integration into the macro-design may be successful or not. The macro-design may contrast ellipses with very pronounced verticals.

In most cases, general 'marks' are far easier and more straightforward to use than letters, unless letters are grouped to form a block or some other shape. Even then, the block or other shape is bound to have irregularities which will be obvious. But to state these difficulties isn't to present an overwhelming case. Overcoming difficulties - triumphing over difficulties - is part of the aesthetic challenge. In fact, there are many word-designs where these seemingly unpromising language-elements are put to very good use in the design.

{diversification} and other {themes}

One design principle which is very important to me is one I call diversification. This involves the attempt to find the alternatives in a design situation. The accepted, the established way of doing things may not be the best. There may be an alternative, or alternatives, which haven't been adequately explored, or which it hasn't occurred to anyone to try out. By thinking in terms of diversification, thinking can become far more flexible and innovative.

It may be the established way of doing things for actions to follow a certain time scale, for example, first to lay down black fabric to kill weeds (action 1) and secondly, after about a year, when the weeds have been eliminated, to remove the fabric and to lay out the beds and paths, surrounding the beds with wooden planks (action 2). But if, instead, action 2 follows action 1 very quickly (put down the black fabric and as soon as possible put the boards in place, and perhaps wood-chippings or straw on the paths) then there are advantages: the fabric won't be moved or damaged by any winds, no matter how strong, there's no need to buy pegs to secure the fabric, there's no need to find and move heavy stones to secure the fabric ('secure' is probably the wrong word - these methods tend to be ineffective.) And, also, the plot looks much neater, is no longer an eyesore. This alternative method is described in the page on 'Gardening Techniques.'

Sometimes, I make the alternatives vivid and concrete by using 'OR.' In the example above, the alternative time scales are: Action 1 - interval of a year - Action 2 (the 'established' method) OR Action 1 - very short interval - Action 2 (the method I use.)

A few other examples of diversification: paths and beds can be fixed OR 'rotatable' (we can rotate beds and paths.) A fruit cage can be separate from the structure which supports the raspberries, the established system, OR combined with it, saving on materials, labour and cost, the method I use. The sides of a composter, the boards which surround beds, may be fixed in position, the established system, OR self-supporting and easily moveable, again, the method I use. I argue, of course, that the alternative to the established system has far more advantages.

Other ideas used in this site include: survey, resolution, separation, alignment, weighting. These ideas are explained at various places in other pages of this site, but for convenience, all the ideas I use are explained here, in one place.

These ideas have many, many applications. A gardener who is choosing a fruit or vegetable or flower variety to plant is applying the ideas. An informed choice of variety is generally very, very important. Later, I mention the advantages and disadvantages of some fruits and vegetables. If you dislike abstract ideas, you'll find that there's a great deal of concrete information here about varieties - although it may be that you're already familiar with it.

A ((survey)) is a listing of the characteristics which are relevant and would include, amongst others:

appearance (of foliage or flower or shoot, including size.)

disease resistance

pest resistance,

cooking qualities

taste (not applicable to most flowers)

time of maturing (early, late or intermediate)

yield

ability to cope with environmental difficulties such as drought

storage abilities (not always relevant)

'shelf life'

ability to withstand the stresses of transportation.

{resolution} involves 'breaking things down.' This has already been done in the case of 'time of maturing' - early, late or intermediate, but it's possible to break things down further. Varieties of potato are described as 'first early,' such as Duke of York and Red Duke of York, 'second early,' such as Saxon, Wilja, Kestrel and maincrop. This is important for the gardener who has limited space. Lawrence D. Hills, in 'Organic Gardening' makes a good case for the planting of Second Early potatoes:

'This class is perhaps best for small gardens, because they can be dug as soon as the flowers are fully open to scrape as new potatoes, or left in to grow larger till the haulm dies down, lifted in August, and stored for the winter and spring.'

'First early' varieties can be resolved in turn. Rocket is perhaps the earliest variety in this group. Maincrop varieties can be resolved into 'early maincrop' and 'late maincrop.' Early maincrop includes: Desiree, King Edward, Maris Piper, Nicola. 'Early maincrop' can be resolved further. For example, valor is a little later than other varieties in this group. Late maincrop varieties include Cara, Golden Wonder, Pink Fir Apple.

{separation} involves the recognition that a variety almost always will not have advantages in all, or most, of these characteristics. In alignment it's falsely assumed that the advantages do all lie with one variety, Isolation focuses attention on one characteristic or facet, or a limited number of them, ignoring others in a survey. Now, I give again the list of characteristics above, with in some cases some advantages and disadvantages for a few selected varieties.

appearance (of foliage or flower or shoot, including size.)

disease resistance

pest resistance,

cooking qualities. Resolution has to be applied. Varieties which are suitable for one use may not be suitable for another. Amongst potatoes, it's widely recognized that the variety Maris Piper is outstanding for making chips. On the other hand, its slug resistance is low, as are scab resistance and drought resistance.

taste (not applicable to most flowers)

time of maturing (early, late or intermediate)

yield

ability to cope with environmental difficulties such as drought

storage abilities (not always relevant)

'shelf life.' Example (for the apple variety Annie Elizabeth). According to Dr D. G. Hessayon, 'No cooking apple has better keeping qualities than old Annie - it lasts for months in store.' On the other hand, its texture is 'rather dry.'

ability to withstand the stresses of transportation.

Weighting gives a preference to one characteristic, or a few characteristics, at the expense of others. So, a supermarket is likely to give a particular weighting to attractive appearance, to shelf life and to the ability to withstand the stresses of transportation, with taste given far less weighting (although things are changing.) A gardener/allotment gardener will give no weighting to shelf life and the ability to withstand the stresses of transportation. A gardener who is aiming to produce vegetables for show will give particular weighting to appearance, including, often, size, but taste is given little or no weighting. Other gardeners will give far less weighting to appearance and far more weighting to taste. If the most weighting is given to taste, then the fact that the variety tends to have low resistance to disease and pests and has a fairly low yield may not be particularly important.

The method of cooking has a great effect on taste, and obviously tastes differ. As with so many other areas of growing and cooking, constructive disagreement is possible. It's often stated that amongst the First Early varieties of potato, Duke of York has the 'best' flavour. This is almost meaningless, unless the method of cooking is stated. It's usually assumed that the method best suited to bringing out the taste of this variety is boiling. It's also stated that Red Duke of York has a similar taste, but superior disease resistance. I've found that the taste of Red Duke of York is nothing special if it's boiled, but definitely something special if it's boiled for about eight minutes, then thickly sliced and sauteed in oil.

{separation}, alignment and some fruit and vegetable varieties

Apples

Alignment isn't full for the variety Arthur Turner but it has many advantages. According to Dr D. G. Hessayon, 'The pink blossom is outstanding - no Apple provides a finer display. Growth is upright and this variety is reliable in northern districts. Crops are heavy and the rather dry texture of the fruit makes it an excellent baking Apple.'

Tomatoes

Alignment isn't full for the variety Shirley but it has many advantages. For me and many other gardeners, this variety's advantages are outstanding. It has good disease resistance, which of course has to be resolved: specifically, it has resistance to leaf mould, virus and greenback. It gives very heavy yields. The taste is good, if the tomatoes are eaten when they are fully ripe (but taste has to be resolved further.) It's sometimes described as 'early.' I've found it to be earlier than, for example, the cherry tomato Gardener's Delight or the beefsteak variety Big Boy, but still not early enough. I give increasing weight to earliness in tomatoes. The common idea that tomatoes can be harvested from early July onwards (or earlier still) isn't borne out by my experience, in South Yorkshire, even in a good season. Harbinger is an old variety which is claimed to be very early. This variety would be well worth trying. If, on the other hand, you give greater weighting to cooking and culinary qualities, then it may be Gardener's Delight (with its sweet, tangy taste) or Big Boy (very suitable for stuffing) which you'll choose.

If any characteristic of fruit and vegetables has to be given the greatest weighting of all, then it's most likely to be taste. The variety Moneymaker fails miserably. Its taste is bland. However, yields are high.

Using these ideas in other areas of gardening

The ideas can be used not just in other areas of gardening but in very many areas outside gardening as well. In gardening, the applications are very varied. For example, they can be used to assess the techniques and methods often recommended. They can even be used to assess organizations.

To begin with an issue raised in the page 'Bed and board:' the problem of slug control. A survey would include these factors: cost, effectiveness, effect on beneficial organisms, effect on the environment in general. Organic growers, I claim, tend to practise isolation, to concentrate attention on the effect on beneficial organisms, and the environment in general - although in the case of this last factor, I'd claim that the response shows disproportion. Of all the forms of pollution, on any scale of pollution, slug-pellets are negligible. Metaldehyde breaks down quite quickly in the soil, and any traces left are not to be compared with the pollutants which reach the soil in massive amounts, such as acid rain.

Expanses are the application in the visual sphere of scale.

What I mean by 'scale' and 'adequacy' can be explained by an unexpected illustration, bullfighting. (But the page on bullfighting makes it clear that my objections to bullfighting - there are many of them - are not based primarily on scale.)

There are no great theatrical masterpieces which last only a quarter of an hour. They need longer than that for their unfolding, to have their impact. Aristotle, in the 'Poetics,' wrote that 'Tragedy is an imitation of an action that ...possesses magnitude.' (Section 4.1) The word he uses for 'magnitude' is μέγεθος 'megethos' and it expresses the need that the dramatic action should be imposing and not mean, not limited in extent. Aristotle's view here isn't binding, but it does express an artistic demand which more than the so-called 'unities' has a continuing force. The 15 minutes, approximately, which elapse from the entry of the bull until its death are far too little for the demands of a more ambitious art. The complete bullfighting session is simply made up of these 15 minutes repeated six times, with six victims put to death. This repetition doesn't in the least amount to magnitude, to 'megethos.' The scale of bullfighting doesn't have adequacy. The scale of Greek drama does have adequacy. Shakespearean themes needed a drama with still greater scale for adequacy.

Ruskin has an extended discussion of scale in architecture in Chapter III of 'Seven Lamps of Architecture,' 'The Lamp of Power.' In 'Mornings in Florence,' 'The Fourth Morning,' section 72, he writes 'Mere size has, indeed, under all disadvantage, some definite value...Disappointed as you may be, or at least ought to be, at first, by St Peter's, in the end you will feel its size...the bigness tells at last: and Corinthian pillars whose capitals alone are ten feet high, and their acanthus leaves three feet long, give you a serious conviction of the infallibility of the Pope, and the fallibility of the wretched Corinthians, who invented the style indeed, but built with capitals no bigger than hand-baskets.'

As for the use of architecture to 'prove' a doctrine, an aphorism of mine is relevant: 'The great achievements of religious architecture, painting, sculpture and literature are no evidence for religion but evidence that people with artistic gifts may have far less talent for critical thinking.' There's no linkage between the power of architecture and the validity of religious beliefs: [power of architecture] > < [validity of religious beliefs]. There's a linkage between baroque architecture and the values of the age of absolutism, [baroque architecture] < > [values of the age of absolutism] but the architecture didn't validate them.

Diversification by simple alternative can be applied to Aristotle's claims concerning magnitude and tragedy, which are justified claims, I'm sure, but undiversified. He claims that there are imitations that have insufficient scale (my term) or 'megethos' (Aristotle's term) and so have inadequacy in imitating the action. What Aristotle didn't consider here (although he did consider very thoroughly similar ethical alternatives in the 'Nicomachean Ethics' ) is the diversified OR: imitations that have excessive scale.

There are many dramatic illustrations of this, from screen and television as well as the stage: imitations where the action is ridiculously inflated, grandiose, in general excessive for the small-minded or insignificant theme.

This too is a claim for disproportion of scale, D H Lawrence on Flaubert's Madame Bovary:

'I think the inherent flaw in Madame Bovary is that individuals like Emma and Charles Bovary are too insignificant to carry the full weight of Gustave Flaubert's profound sense of tragedy...Emma and Charles Bovary are two ordinary persons, chosen because they are ordinary. But Flaubert is by no means an ordinary person. Yet he insists on pouring his own deep and bitter tragic consciousness into the little skins of the country doctor and his dissatisfied wife...'

I live in a small terraced house, which suits me but would have insufficient scale for a King or Queen, even the unpretentious royalty of the Netherlands or Denmark. Excessive scale is represented by the inhuman scale of brutalistic architecture for accommodation.

It's necessary to diversify further: excessive scale can be justified OR unjustified. Brutalist architecture, which has the effect of making people more insignificant, is an example of unjustified excessive scale, I think. There are compensating advantages in some excessive scale. Baroque architecture makes people less significant rather than more significant, but it has a compensating drama, energy, dynamism, excitement. Neo-classic St Petersburg is built on an inhuman scale but the scale enhances human experience. This, and the Baroque excessiveness, has a linkage with the excess (the 'nimiety') of Beethoven in some of his works, such as the repeated figure in the Scherzo of his Quartet Opus 135: an example of artistically justified excess and great scale in a small-scale musical genre.

An example of an expanse, a wheat field, a glorious sight, more likely to

be a glorious sight if vision, ocular vision, is amplified, intensified by

inner vision. One means would be this, from 'Centuries of Meditations,' by

the part-visionary part-deluded poet Thomas Traherne:

'The corn

was orient and immortal wheat, which never should be reaped, nor was ever

sown. I thought it had stood from everlasting to everlasting.'

Or, more likely to intensify the experience of looking, the music and the lyrics of this, 'Fields of gold,' by Sting:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dnj1zshmTE0

'Will you stay with me, will you be my love...among the fields of barley...?'

And, also, the wonderful images of the fields of gold, the fields of barley.

The distracting tapping of the percussion makes the music slightly less wonderful (is {restriction}: [the music]) but remembering can subtract it.

An expanse may be too plain, lacking in visual interest because lacking in visual detail, or its impact can be restricted by details. This is the case in this image, I think, which shows a wheat field in Hungary:

The ears of wheat are at varying angles and in this case, variation is {restriction}: [aesthetic impact]. The effect is restless, unsatisfying. The colour isn't, of course, particularly golden but rather drab gold. The distant hills do, though, form a satisfying contrast with the field of wheat, and they have adequate scale.

I'm not in the least so preoccupied with the visual impact of fields of wheat or fields of barley that I forget their practical importance. I've a strong interest in baking, using wheat flour - there are many other kinds, of course - and in brewing, using malt from barley.

In my growing, again and again I come up against the competing demands of visual interest - including the creation of beauty or the striving to create beauty - and functionality. I don't grow wheat or barley but I grow many other crops. This is a bed used for growing potato plants, from my page Gardening / construction: introduction, with photographs:

.jpg)

In previous years, potatoes have been grown in beds, with paths between the beds, using the system described on the page Beds and boards.

This system has practical advantages, such as avoidance of the need to walk on the beds, which compacts the soil to some extent. It can be used in such a way as to give visual interest - a succession of rectangular beds of the same size along an axis can amount to a compostion with the satisfying regularity of some abstract art. If the bed is long or quite long, it can amount to an expanse in its own right, but it isn't likely to have scale as satisfying as the scale of a more substantial expanse.

An expanse may be unsatisfying to a very significant extent or to some extent because it has insufficient contrasts, or the contrasts are repetitive or otherwise unsatisfying. So many works of modern architecture have this defect. To give one example, this is the Arts Tower of Sheffield University (there are much worse University buildings nearby):

Absolute size is a criterion for deciding whether an element qualifies as an expanse, but greater size may not necessarily make for a more satisfying expanse or an expanse with greater impact. A further consideration is scale in the sense of relative proportion.

William Wordsworth, in his 'Guide to the Lakes,' wrote very well about scale, scale as size and scale as relative proportion - as he did about so many other aspects of the landscape of the Lake District, in the section 'Alpine scenes compared with Cumbrian:'

' ... we have mountains, the highest of which little exceed 3,000 feet, while some of the Alps do not fall short of 14,000 or 15,000, and 8,000 or 10,000 is not an uncommon elevation. Our tracts of wood and water are almost as diminutive in comparison; therefore, as far as sublimity is dependent upon absolute bulk and height, and atmospherical influences in connexion with these, it is obvious hat there can be no rivalship. But a short residence among the British Mountains will furnish abundant proof that after a certain point of elevation, viz. that which allows of compact and fleecy clouds settling upon, or sweeping over, the summits, the sense of sublimity depends more upon form and relation of objects to each other than upon their actual magnitude; and that an elevation of 3,000 feet is sufficient to call forth in a most impressive degree the creative, and magnifying, and softening powers of the atmosphere.'

He goes on to make other claims which are very compelling, I think, including ones to do with plants - trees of many kinds, including the olive, and the vine.- and lakes.

A skyline is a composite, a collection of objects in which the linkages between the objects is important. In a garden, we can't hope to emulate the impact of the skyline - or the skylines - of Oxford or Manhattan, but a garden can have a distinctive skyline.

Nikolaus Pevsner on avoidance of congestion ('Cambridgeshire,' 'Clare College'):

We must now for a moment return to Trinity Lane. The architectural grouping here is superb, with King's College Chapel, the New Schools and the E front of Clare set back behind the Gateposts of 1675. These were carved by Pearce. There is much variety here in a narrow place, without any congestion.'

The long diagonal in the image above is the walkway I constructed to avoid the problem of walking in a muddy morass to get down into the allotment when rainfall has been heavy for a long time. The walkway can be viewed as part of the skyline, perhaps - it underlines part of the skyline.

Nikolaus Pevsner on the skyline of Oxford ('The Buildings of England,' 'Oxfordshire,' Introduction):

' ... Cambridge has no skyline, Oxford has the most telling skyline of England, though dreaming spires is nonsense in every respect. Surely, in spite of St Mary, All Saints and the cathedral, and now Nuffield, Oxford is remembered less for them than for Tom Tower, the Camera and Magdalen tower. It is the variety of shapes which makes the skyline.'

The shapes which make up a garden skyline can have a variety of shapes too, including small spires - if not dreaming spires - the pyramids of canes supporting climbing beans, and including greenhouses (like sheds, utilitarian objects but with less utilitarian associations than sheds), and some objects I include in this skyline, a support star and a hop pole. The variety can include narrow as well as broad structures.

This is a view of a small spire - the pole supporting the hop plant - with cane pyramids supporting runner bean plants and a view of the school, but from a different position, from above, looking down: a far more satisfying view than the one shown above, but with flaws: there's congestion, the runner bean pyramid to the right is too near the hop pole. Here, I gave greater weight to crop production than to aesthetics.

From the book 'The Garden Planner,' Consultant Editor Ashley Stephenson, the section 'The Japanese Garden,'

'Shakkei, or borrowed scenery - a glimpse beyond the garden of hills, perhaps, or mountains, trees or roofs, - is incorporated into the design and makes the garden seem larger.'

Here, the light coloured expanse of the roof of the school buildings contrasts with the darker walls and roof belonging to the same borrowed scenery, and with the dark spire, not an expanse, in this part of the growing area. There are other obvious contrasts, including contrasts of height and bulk. The spire is much shorter than the school buildings but the base is higher..

The components which make up a composition - a musical composition or a visual composition such as a garden - may have aesthetic appeal or aesthetic strength in a scale from non-existent to very great, such as an individual flower, but a musical composition or a garden may have very great aesthetic appeal or aesthetic strength despite the components lacking marked aesthetic strength.

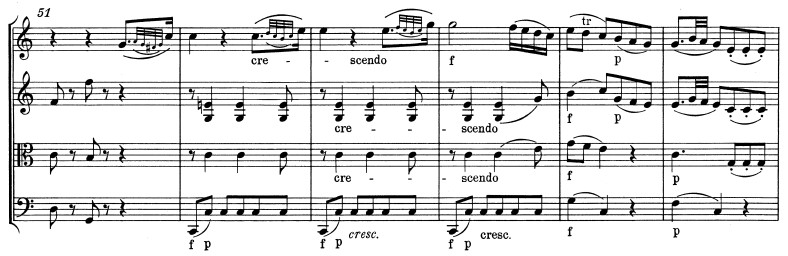

In 'Mozart's Chamber Music,' A. Hyatt King writes of the andante of Mozart's String Quartet K 387,

'... Mozart moves to the calm of C major, and pours forth a stream of rapt, contemplative music, righ in gruppetti, soaring fioriture and beautifully calculated climaxes. It is a remarkable example of the sustained, exalted feeling expressed with wonderful harmonic resource, yet without a single melodic phrase that is at all memorable in itself.'

This is the opening of the wonderful Andante of this wonderful composition:

The opening of the rondo of Beethoven's Waldstein sonata Op. 53 have a similar unhurried calm, at a faster tempo.

Timing and the spoken poem

Tim Love discusses 'Notation in Poetry and Music' at http://www2.eng.cam.ac.uk/~tpl/texts/notation.html and claims, rightly, that in poetry, 'the paucity of auxiliary notation is surprising.' Here, I suggest one simple kind of auxiliary notation: a timing.

Compact disks of recorded music have timings for the individual tracks. In the same way, many of the poems on this site have a timing in seconds (s). The timing provides useful information about the spoken poem.

Of all guides for the interpreter, an approximate timing, in seconds, of the complete poem is the simplest. A timing gives information about the poet's interpretation of the poem, or one of the poet's interpretations. Of course, the timing can be disregarded, like a composer's metronome marking. Different timings for a poem are a clue to different interpretations of a poem. Within the timing are accommodated the surges, the climaxes, the giving of weight to words, the significant pauses. Poems, like pieces of music, have, surely, a 'tempo giusto' as well as interpretations of the spoken poem that are insensitive or ludicrous simply because the timing is arguably faulty.

I have two recordings of Beethoven's Symphony Number 6, the Pastoral. Both interpretations seem to me to be badly flawed, in particular the interpretation of the first movement, which bears the title 'Awakening of joyful feelings on arrival in the country.' One interpretation (by Harnoncourt) conveys very little sense of joy because it's too slow, ponderous, sluggish. The other (by Hans Swarowsky) conveys little sense of joy because the movement is rushed. The timing for the first movement in the first version is 13.07 min. and the timing for this movement in the second version is 10.57 min., a significant difference. I'm sure that an artistically successful interpretation of this movement, one at the 'tempo giusto,' must lie between these two, at something like twelve minutes. A timing, then, conveys a great deal about an interpretation.

It's obviously essential to go beyond the timing and to take account of many fine details. Some performances may reveal depths, or telling details, which other performances and recordings don't bring out at all. A slight, insensitive hesitation at one point may be enough to diminish the artistic impact of the work

A gifted interpreter shapes the poetic phrase as sensitively as a gifted singer, instrumentalist or conductor shapes the musical phrase. A musician won't rely on the inspiration of the moment to interpret the score, but will make a careful study of it. In the same way, the interpreter of poetry must study the text thoroughly. The methods of analysis I propose should be helpful in this preliminary work.

Composers have available a notation to give guidance on such matters as tempo and dynamics - allegro, andante, forte, piano, and so on. A notation - necessarily much more simple than the musical one - to guide the interpreter of spoken poetry would be useful.

I would like to see informed comment on different recordings of poetry - before that, of course, the making of different recordings. Even more important, there's the need to foster poetry readings, and the need to respond to spoken poetry with some of the sophistication and intelligence to be found amongst music critics and drama critics, when they consider different interpretations of the same score or text, finding some interpretations searching and very significant, others, perhaps, mannered or pretentious.

[Supplementary: timing in performances of Mahler.]

Tony Duggan makes a very interesting use of timings in his criticism of a performance of Mahler's Fifth Symphony (not a recording but a performance conducted by Simon Rattle at the Proms in 1999). He compares the timings for the movements in this performance with the timings for a performance of Boulez on Deutsche Gramophon (Boulez' timings in brackets below):

1. 11.42 (12.52)

2. 12.57 (15.02)

3. 14.56 (18.12)

4. 8.15 (10.59)

5. 13.46 (15.12)

The comments of Tony Duggan below relate to Simon Rattle's performance. To produce the timings above he had to use a stopwatch! This is a memorable instance of the fact that a concern for the technical need not be in conflict with a passionate concern for artistic success and failure, in this case with a passionate concern for conveying Mahler's vision.

"The faster tempo effect was clear right from the beginning in tonight's performance. The Funeral March, so important in establishing the mood of tragedy out of which the contrasts that Mahler is setting up to be resolved emerge, sounded at this speed more wistful than tragic. This was even accentuated by the slightly clipped articulation of the strings, beautifully prepared let it be said, but ultimately surely too careful. I know that in these crucial opening bars what I think Mahler intended was something more weighty and overwhelming...

"The second movement was very fast indeed and here I was reminded of Bruno Walter to start with. There is, of course, a case to be made for the vehement sections to go at a furious pace. However, the conductor should know when to contrast this with a slower tempo when needed, notably the great cello lament. It isn't a question of it being pulled around and moulded, this unforgettable passage ought to contrast more with the maelstrom around it and Rattle failed again to mark this.

"I suppose the performance was still capable of redemption at this point. All hinging on the Scherzo. So it is with regret I have to report that here, for me, Rattle finally blew it. Mahler is on record as saying he knew conductors would ruin this movement by taking it too fast and he was surely right. The performances that are a success are surely the ones that can reconcile overall structure with inner detail, making the listener aware of the episodic nature of the piece, the peaks and troughs, the passages of solitary contemplation set against the passages of wild abandon. Alas, at Rattle's breakneck speed any hope of paying more than a passing nod to the narrower paths of this great movement were doomed...

"The tempo for the Adagietto was, for me, perfect. Would that all conductors could take it at this kind of speed and with this kind of simplicity. The nobility and beauty of the movement is surely enhanced at a flowing tempo..."

And he ends with, "Now, where's my Barbirolli?"

Phrasing is as important to the interpreter of a poem as it is to the singer, instrumentalist or conductor whose concern is to make the interpretation of the written score as expressive as possible. I've introduced a technique, sectional analysis, for the study of the linkage between the line of poetry, the phrase and the sentence.

I use the term 'sections' to refer to different phrases (present as a whole or in part) in each line, and I use sectional analysis to study the relationship between sections, and in so doing the relationship between lines and phrases. Square brackets are used to enclose phrases. These brackets may be opened and closed within one line, or they may be opened in one line and closed in another. I also refer to 'opening the phrase' and 'closing the phrase.' I apply sectional analysis to some very great lines of 'The Prelude' (lines 452-457, 1805 version) In all the lines except for 454 there are two sections.

452 [And in the frosty

season,] [when the sun

453 was set,] [and visible for many a mile

454 The cottage windows through the twilight blazed,]

455 [I heeded not the summons;] [happy time

456 it was indeed for all of us,] [to me

457 it was a time of rapture.] ...

In this extract, short though it is, there's a very effective contrast of phrase length. Shorter phrases are contrasted with the longer phrase which is opened in line 453 and closed in line 454. Line endings may divide the phrase or not: the phrase. 'And in the frosty season' and the phrase 'when the sun was set' are different in the way in which they are linked with the lines. The first phrase is divided, the second is not.

As regards meaning rather than sound, there are remarkable contrasts to do with the meaning of the phrases, giving to the whole passage an overwhelming sensuous immediacy. Each phrase has a dominant theme. Here, I draw attention to words within the phrases:

"frosty

season" - cold

"sun was set" - light turned to darkness

"through the twilight blazed" - lighting up the darkness

"happy time" and "a time of rapture" - happiness and an

intensification of happiness in the next phrase

"clear and loud" - sound

Sectional analysis and phrase analysis are ways of aiding the appreciation of phrase rhythm in poetry, the counterpart of expressive prose rhythm, and, like the rhythm of stressed and unstressed syllables, contributing to the overall power and beauty of a poem. A close study of phrasing is also useful for the interpreter, who tries to make the spoken poem as effective as possible.

It

would be an interesting study to carry out sectional analysis on a great number

of lines of poetry in pentameters to find out if it's more common for lines

to be divided into sections by the ratio of 2:3 (or 3:2) feet than by the

ratio of 1:4 (or 4:1) This study of poetic ratio belongs to the

neglected field of

quantitative poetry criticism. The study of ratio is well established in architecture and the fine

arts. The best known example of ratio concerns the 'golden section.' The golden

section is defined in terms of a line divided in such a way that the smaller

section is to the greater as the greater is to the whole. It can also be defined

in terms of the proportion of the two dimensions of a plane figure. The golden

section can't be calculated in exact mathematical terms, but is approximately

5:8 (the ratio above of 2:3 is closer to this than 1:4, of course.) A great

many artists and architects have used the golden section, consciously or unconsciously.

The proportion between exterior and interior in a zoned poem is another instance

of poetic ratio. The harmony of a great painting or a great building may be

linked with mathematical relationships.

In general, '...wherever Proportion exists at all, one member of the composition

must be either larger than, or in some way supreme over, the rest. There is

no proportion between equal things.' (Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture,

IV 26.)

In his discussion of the first paragraph of 'Tintern Abbey' in his book 'The Passion of Meter: A Study of Wordsworth's Metrical Art,' Brennan O' Donnell provides this note (P. 271):

'In Wordsworth's careful structuring both of this introductory verse paragraph and of the poem as a whole - particularly his gradual accumulation of descriptive detail and his amassing of smaller formal structures into larger and more comprehensive structures - Lee M. Johnson has found evidence that Wordsworth constructed the poem according to strict geometrical proportions: " "Tintern Abbey" is a modified Pindaric ode in the form of a double golden section, which is built upon the lesser details of repeated images and the ornamental patterns of misple binaries" (Wordsworth's Metaphysical Verse, 60).

The contrasts that are so common within single works of music are very instructive. In classical sonata form, the slow movement of a symphony, concerto, string quartet or sonata may be an adagio, the finale very much faster: molto allegro or presto. There may be differences of tone which are equally marked: to give just one example, the second and fourth movements of Beethoven's Eroica symphony. There are analogues in poetry for musical contrasts of tempo and contrasts of tone, but not for contrasts of key.

In general, the use of contrast in music is instructive for students of poetry, but so also is music's use of repetition. This is despite the fact that one procedure in classical music would be unthinkable in poetry: repetition of a sizeable block, the repetition of an entire exposition section in sonata form ('block' including music at its most inspired). Repetition in this one context should not lead us to believe that exact repetition is common in other musical contexts. The classical composer uses such differences as differences in instrumentation and the all-important differences of tonality to deflect exact repetition.

Classical music is strongly directional, the music drawn towards the closing chord as strongly as water drawn towards a waterfall. Repetition of an exposition section has to be understood in the context of directionality. The development section which follows the exposition will be strongly directional. Repeating the exposition makes the listener more fully aware of what the listener knows will be developed and given further direction. This is repetition with expectation.

Repetition in poetry doesn't serve the same structural (and dynamic purposes). In such a directional art, repetition is anti-directional, not, as in sonata form, the prelude to further momentum. This is repetition as a series of reminders of a first occurrence.

The size of the repeated element is less important than the number of repetitions. The exposition section is repeated once. When repetition takes place in poetry, it is often much more than twice. Yeats repeats the line 'Daybreak and a candle-end' seven times in his poem 'The Wild Old Wicked Man.'

I think that almost all repetition in poetry is problematic. To begin with the final stanza of Blake's 'The Tyger.' This is an exact repetition of the first (except for the substitution of 'Dare frame' for 'Could frame.') This repetition cannot be counted a success in this otherwise magnificent poem. (Blake's design for this poem is another weakness - the picture is tame and devoid of power.)

It's difficult to achieve artistic success even with repetition of short elements, such as a single line. In general, the more obvious the repetition the less the artistic success - although the overall success may be very great. In the same way, the more obvious the rhyme, the less the artistic success. Deflecting attention from a repetition in poetry is valuable, as was deflecting attention from a repetition in classical music.So also is naturalness of repetition, the seeming inevitability of repetition. This is one of the reasons why I admire the villanelles of Jared Carter, which I discuss in the page on Modulation.

Few if any great poets have used repetition of lines as much as Yeats, one of the twentieth century poets I most admire, and I think that in every case, the repetition diminishes the artistic success of the poem. Just a few examples:

'Crazy

Jane On God' and repetition of

All things remain in God.

'Crazy Jane Grown Old Looks At The Dancers and repletion of

Love is like the lion's tooth.

'The

Curse of Cromwell' and repetition of

O what of that, O what of that,

what is there left to say?

'The

Wild Old Wicked Man' and repetition of

Daybreak and a candle-end.

'The

Pilgrim' and repetition of

'fol de rol de rolly O' (preceded by 'Is,' 'But,' or 'Was.'

'Long-legged fly' and repetition of

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

His mind moves upon silence.

Yeats

uses repetition on a larger scale than repetition of one or two lines. In

'Three Marching Songs' there's repetition of four lines in each of the songs.

In the second, there's repetition of

What marches through the mountain pass?

No, no, my son, not yet;

That is an airy spot

And no man knows what treads the grass.

Almost half of the thirty-one lines of the intolerable poem 'I Am Of Ireland' consists of the repeated lines

'I

am of Ireland,

And the Holy Land of Ireland,

And time runs on,' cried she.

'Come out of charity,

Come dance with me in Ireland.'